| This is Bloomberg Opinion Today, ideas brought to life by the labor and talent of Bloomberg Opinion’s opinions. On Sundays, we look at the major themes of the week past and how they will define the week ahead. Sign up for the daily newsletter here . Two big things happened in my life this week. One was President Donald Trump’s threat to enact a 100% tariff on films made in other countries because “WE WANT MOVIES MADE IN AMERICA, AGAIN!” The other was the “tremendous,” “fantastic,” “historic” and “comprehensive” (read: sorta, kinda, maybe, let’s hash this out later) trade deal Trump hammered out with UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer. Why my life, though? Because of Midsomer County, of course. I am among an elite group of Americans to have endured all 140 episodes (and counting) of the UK detective series Midsomer Murders, set in a verdant, charming, picturesque South England county that, by this point one assumes, has had one half of the population slaughtered, with the other half in jail awaiting trial. Don’t get me wrong, it is not a good show. You’d never find it in the pantheon of British mystery series, which begins with Helen Mirren’s Prime Suspect, followed by Life on Mars, Happy Valley, Line of Duty, Sherlock, Inspector Morse, Luther, Broadchurch (season one, anyway) [1] and a a few others. Rather, Midsomer is down there with the moribund Agatha Christie remakes and just above, eek, every “cozy mystery” ever made (Lord, spare me from another season of Agatha Raisin.) [2] At first, given that Trump talked specifically about movies, I was only mildly worried: Not a whole lot has come out of Britain on the feature front since the golden age of Get Carter, The Long Good Friday (more Helen Mirren!) and Mona Lisa. But I got nervous when White House spokesman Kush Desai pointedly refused to specify whether television would be subject to the penalties, and fell into pure panic when I saw the headline, “Trump plans $100m tariffs on movies and TV shows made overseas” at the Independent. Will Acorn TV and BritBox have to charge me double for my 2.8 murders per Midsomer episode? That’s an expensive proposition given the pure abundance of them:  Fortunately, we have Bloomberg Opinion to calm me down. While Trump’s right that producers take advantage of lower costs and big tax breaks in places like Canada and London, the question is whether trade penalties could stop it. “How would one even impose a tariff on ‘movies’?” asks Jason Bailey. “Movies are comprised of ideas brought to life by the labor and talent of skilled professionals, and more often than not these days, they’re digitally transmitted — not contained in a physical form. Does he want to tariff ticket prices? Does he propose making Blu-rays for foreign films twice as expensive? What about streaming services, which typically fill out their catalogs with international programming?” Lots of unanswered questions there. But then, the US-UK trade deal seems to be all about unanswered questions. “It’s not a deal but rather a framework for an agreement. In other words, US and UK negotiators still have a lot of work to do in coming weeks (perhaps months or even years like these things usually take?) to hammer out the details,” writes Robert Burgess. “More importantly, what was announced fails to accomplish any of the three objectives Trump originally put forward leading up to April 2’s ‘Liberation Day’ for levying tariffs on America’s trading partners.” Our London correspondents aren’t chuffed, either. “The reality of what’s been unveiled on Thursday doesn’t match the superlatives flowing out of the Oval Office,” write Lionel Laurent and Marcus Ashworth. “The total economic impact for the services-centric UK of these new tariffs is probably about 0.1% of gross domestic product, according to Bloomberg Economics. You’d have to squint very hard to see this as a game-changer for the US or global trade, too … this all feels like the end of the beginning, rather than the beginning of the end.” Allison Schrager has a contrarian take: that the tentative pact accomplishes a great deal, albeit not in the way Trump intends. “While a 10% tariff isn’t much of a win — it’s about three times the average for developed countries — a reduction of non-tariff barriers is something worth bragging about,” she writes. “Non-tariff barriers, called NTBs, are regulations that restrict trade and make it harder or more expensive for foreign firms to sell goods and services in a given country. By bringing attention to them, Trump is doing the world a service, since they are costly for all involved — especially the country that enacts them. In that sense, the real winner in this deal will be the UK.” (On the flip side, Britain is shooting itself in the foot by changing tax rules that will drive away rich foreign residents who “pay large amounts of tax, enrich the economy with their entrepreneurial talents and fund philanthropic works,” writes Matthew Brooker.)  Allison also has a mystery of her own to solve: Why aren’t markets pricing in the possibility of a recession? “Are traders deluded? Irrational? Or do they know something that too many prognosticators do not — namely, that tariffs will not bring about an economic calamity,” she explains. “Recessions tend to be caused by some shock to the economy — a sudden and very large trade change, a financial crisis, an unusually bad economic event. That’s the recessionary risk of tariffs: They may not be enough to cause a recession, but they will make the economy less resilient to whatever shock comes along.” Speaking of shocks: Another surprise winner last week was globalization. This was due to a different UK trade deal, one with India, according to Mihir Sharma. “It is refreshing in today’s climate to hear people in power talk up the benefits that consumers gain from trade. And they will definitely do well out of this deal,” he writes. “Perhaps New Delhi’s concessions to Britain are a glimpse of what it will offer Trump. And perhaps the need to hand such concessions to the US made it easier to give them to Britain. It would be ironic if tariff-loving Trump turns out to be the person who pushes India, Asia and the rest of the world to overcome their hesitations about trade.” That would be great, sure. But my biggest hope for any US-India pact: it spurs one of the big streaming services to pick up Satyajit Ray’s classic private eye series Feluda. [3] It has a relatively small body count but a great detective: I don’t think it would take long for the Sherlock Holmes of West Bengal to put an end to the bucolic bloodbath in Midsomer County. Bonus Rough Trade Reading: What’s the World Got in Store ? - US CPI, May 13: Stagflation, But That's Not Important Right Now — John Authers

- Trump Middle East trip, May 13: Saudi Arabia Goes Whistling Past the Kazakh Oil Graveyard — Javier Blas

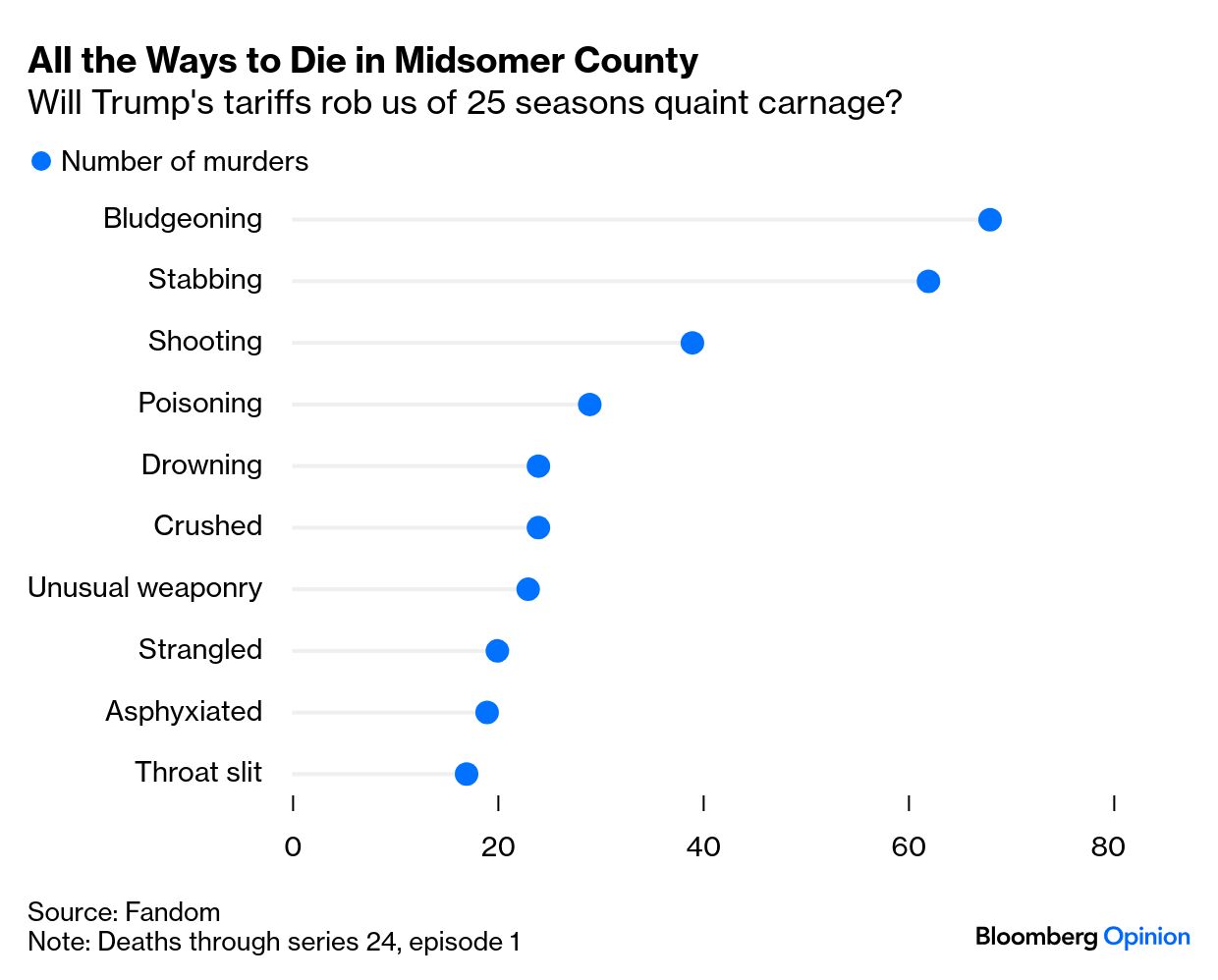

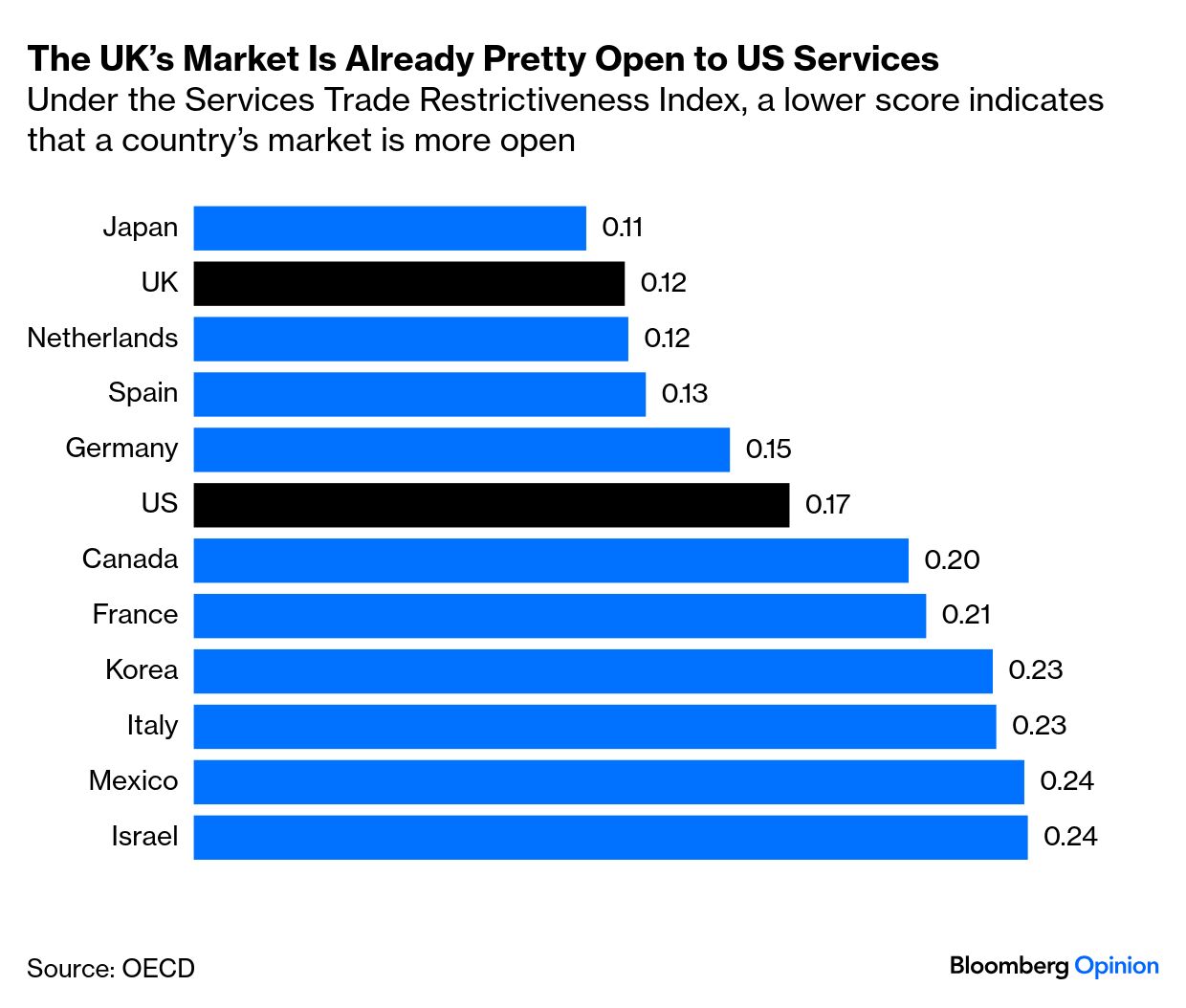

- Walmart earnings, May 15: Can CEOs Really Have Private Lives? — Beth Kowitt

I happened to be in London on Nov. 11, 2014. This was not only the holiday the Brits call Remembrance Day and we Yanks call Veterans Day, but it fell one century after the beginning of the war that didn’t end all wars, World War I. So I put a felt poppy on my lapel and paid homage at the finest war memorial in the world, Edwin Lutyens’s Cenotaph: [4]  An empty tomb full of sorrow. Photographer: Alishia Abodunde/Getty Images VE Day, marking the end of World War II in Europe, seems an afterthought in comparison; it’s not even celebrated in the US. But Thursday was significant: the 80th victory anniversary of the war that ended all wars in Europe (until Russia’s Vladimir Putin came along). “In Britain, VE Day was marked by street parties, bunting and waves from King Charles III from the balcony of Buckingham Palace. It all felt a bit hollow, when seven days earlier a plurality of those taking part in local elections voted for the anti-immigrant, nationalistic Reform,” writes Rosa Brooks. “Atop it all in the White House sits a man so ignorant of history that his VE Day social media post featured the raising of the flag on Iwo Jima, symbol of the war in the Pacific that continued to rage on May 8 and would do so for another three months. The erosion of democracy feels so pervasive yet so incremental, it’s hard to know how to respond.” Meanwhile, at Moscow’s Victory Day military parade, a couple of comrades in arms — Putin and Xi Jinping — were trying to turn that erosion of democracy into a landslide. Some US foreign policy mandarins have suggested that the bromance could be broken by a “reverse Kissinger”: pulling Russia away from China, as former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger supposedly pulled China away from the Soviet Union in the 1970s. Worth a try, but Hal Brands is skeptical. “Splitting rivals is a time-honored strategic tradition. But as Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s trip to Moscow this week affirms, the Sino-Russian relationship won’t be broken anytime soon,” Hal writes. “The strategic unity of the world’s leading revisionist states is profound. Moscow and Beijing are trying to create a radically different international order — one in which American power is battered, American alliances are broken, and autocracy reigns because democracy’s global dominance has been shattered. Both know, moreover, that they cannot defeat the US if they are simultaneously trying to defeat each other.” I suggest that next May 8, the pair go to London and think about that terse inscription on the Cenotaph: The Glorious Dead. That’s what happens, as we saw twice in the 20th century, when autocrats try to break up the democratic world. Notes: Please send Parson Russell Terriers and feedback to Tobin Harshaw at tharshaw@bloomberg.net. |