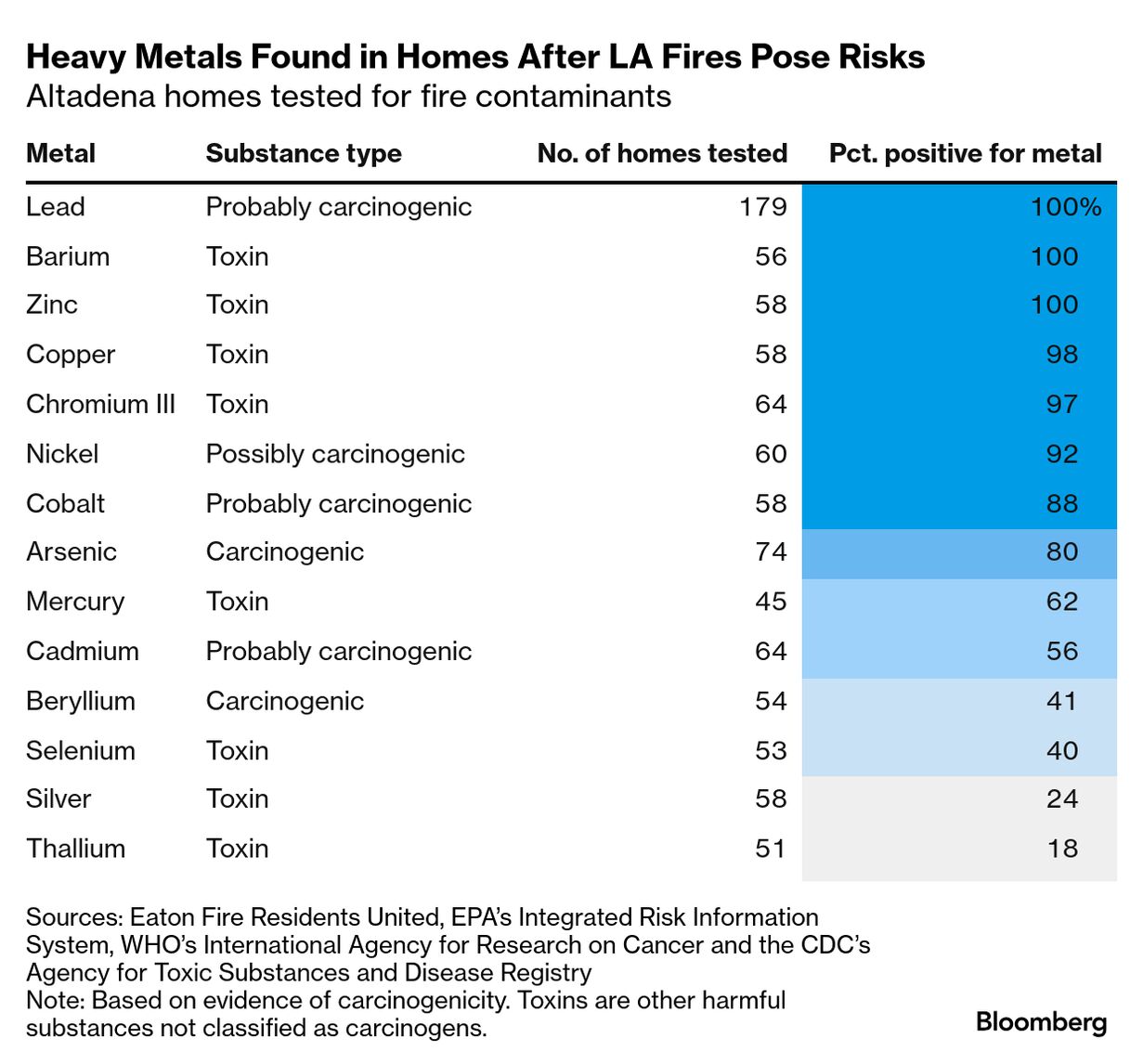

| By Emma Court At a church parking lot near Los Angeles, two hazmat-suit-clad workers vacuumed and wiped most of the contents of Elle Schneider’s house. Surrounded by stacked plastic bins of books and clothes, they opened up the drawers of a squat wooden dresser and swabbed the outside of a tall white cabinet. The blaze that ravaged the LA suburb of Altadena in January stopped some 50 feet short of the freelance cinematographer’s home, but its plumes filtered through doors and windows, leaving behind lead and other hazardous substances. “It’s embarrassing and it’s dehumanizing to have to do this in front of the entire neighborhood,” said Schneider, who relied on the makeshift remediation center at the church to clean many of her belongings. “It’s bad enough to have to throw out so much of your stuff.” Months after the smoke from California’s destructive fires cleared from LA skies, residents are still reckoning with a toxic stew of smoke pollutants whose effects on human health are poorly understood. Without federal and local standards on how to deal with contaminants like arsenic and the carcinogen benzene, dozens of researchers and private specialists are combing through yards and homes. “‘What are we facing? What are we exposed to? Is it safe?’ We hear these questions all the time,” said Yifang Zhu, a professor at the University of California at Los Angeles’s public health school who’s been measuring pollution related to the fires since early this year.  Zhu, left, and a postdoctoral researcher collect pillows at a home in the Pacific Palisades. Photographer: Alex Welsh/Bloomberg It’s an unprecedented research effort made more challenging by pre-existing contamination, but urgent as wildfires increasingly spill into communities fueled by climate change. Unlike fires in wilderness areas, which mostly consume vegetation, urban conflagrations suck up buildings, cars and their contents, spitting hazards well beyond the burn area. Some experts say the health risks could be akin to those of 9/11’s toxic dust, though research is still early. California’s insurance commissioner created a task force earlier this year to come up with best practices for smoke claims, but the group doesn’t expect to issue recommendations until early next year. “In the absence of established standards, site-specific smoke damage remediation will need to be guided by the professional judgment of qualified experts,” a LA County Department of Public Health spokesperson said. A slew of testsInside a burn zone in the Pacific Palisades, Zhu and two postdoctoral researchers bagged throw pillows from a still-standing home to test for volatile organic compounds, which pose health risks like respiratory issues and cancer. So-called wildland-urban interface fires now make up a larger share of blazes. Lingering pollutants in still-standing homes can pose similar risks to active wildfire smoke. After a wildfire the size of the ones in LA or Lahaina, Hawaii, the federal government usually removes hazardous materials, debris and up to several inches of soil from burned areas. But it has traditionally worked in places damaged by flames, not smoke. The US Environmental Protection Agency and Federal Emergency Management Agency advise homeowners to mist before sweeping and to use HEPA vacuums. LA County’s public health department has warned those living near burned areas about exposure to heavy metals, asbestos and chemicals, but current testing is mainly limited to lead in soil. Independent researchers say there’s far a lot more to be concerned about. Data from private homeowner tests compiled by Eaton Fire Residents United, a nonprofit advocating for locals, showed that nearly 20% of 129 homes that screened for it had asbestos. Testing also detected nickel, arsenic and even beryllium, a carcinogen that could have come from computers’ copper wiring or the aluminum in burned cars.  “We really don't know long-term effects,” said John Balmes, a physician at University of California at San Francisco and UC Berkeley emeritus professor. The EPA and LA County’s public health department said there are currently no guidelines for gauging the risk of these chemicals when they come from wildfire smoke. Homeowner decisionsTesting a home after a wildfire can cost around $2,500 to $20,000. Nicole Maccalla was billed $83,000 for remediation. Her insurer will only cover a portion of the cleaning, she said. She and her family moved back into their Altadena home, but soon her pets fell sick, and recurring headaches that had long plagued Maccalla also became constant. “Would I rather live somewhere I love and die a little sooner, or live somewhere that is not home to me that I don’t like, and live longer?” said Maccalla, a data scientist who’s been overseeing testing data processing and mapping at Eaton Fire Residents United in her spare time. Compared to owners who lost their houses to the flames, there are fewer resources available for residents with homes polluted by smoke. “People whose houses didn’t burn down are in worse shape than people whose houses did,” said Jane Williams, executive director of California Communities Against Toxics. The health effects of exposure to chemicals lingering after fires are also less understood than those of direct wildfire smoke. The risk is “potentially people going back into those homes if they’re not properly remediated and getting an ongoing toxic dose,” said Michael Jerrett, an environmental health sciences professor at UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health. Health concerns range from headaches to lower IQ in children, higher risk of pregnancy complications and cancer, he said. Symptoms like Maccalla’s are common, with about a third of around 1,200 households in the vicinity of the LA wildfires reporting at least one physical health symptom, according to a survey led by Andrew Whelton, a Purdue University engineering professor. Worryingly, there is evidence that pollution can stick around even after cleaning. One certified industrial hygienist told Bloomberg Green that at LA area houses she’s tested, she’s recommended gut renovations, leaving little of the original house but its wooden framing. Some of the scientists studying the public health implications of the LA fires have called for better monitoring of those affected. The LA Fire HEALTH Study, a research team that includes Zhu and Jerrett, is tracking 50 affected homes and their occupants, a costly effort that involves taking measurements at the residences and collecting blood, hair, nail and urine samples from the residents over time. The hope is that work will help reduce how much damage is done by future fires. For Schneider, the cinematographer who’s still in temporary housing, there’s no question about the stakes. Growing up in New York City, her brother attended high school blocks away from the site where the Twin Towers once stood. He later developed lymphoma, which Schneider and her family suspect was because of exposure to the disaster’s toxic dust. “I understand what happens if you don't remediate properly,” she said. Read the full version of this story for additional detail on the health risks in LA area homes and how they reveal gaps in the government wildfire response on Bloomberg.com. |