|

A Nobel for thinking about long-term growth

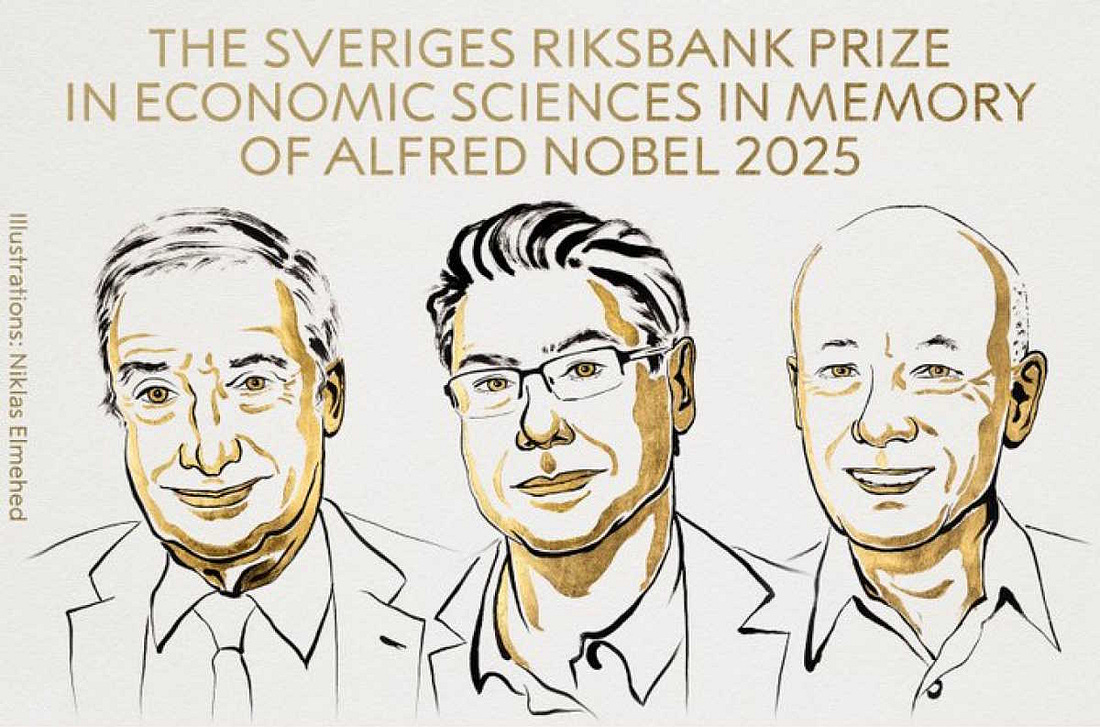

Aghion, Howitt, and Mokyr tackled the biggest question of all.

Well, it’s time for my annual Economics Nobel post! If you like, you can also check out my posts for 2024, 2023, 2022, and 2021.

Other than the tired old question of whether the Econ Nobel is a “real” Nobel prize,¹ there are basically three things to talk about in these posts:

The research that got the prize

What the prize says about the economics profession

What the prize says about politics and policy in the wider world

So first let’s briefly talk about the research. This year’s prize went to Joel Mokyr, for writing about culture and growth, and Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, for making models of technological innovation. For good summaries of what this prize is all about, see:

The Nobel committee’s own explanation

Alex Tabarrok’s post, mostly about Aghion and Howitt

Kevin Bryan’s post about both winners

Anton Howes’ post about Mokyr

I’m personally much more familiar with Aghion and Howitt’s work, so let’s start with that. The main idea they won the prize for is a model of how competition drives innovation, which they published in 1992.

The basic idea of this model is that technologies become obsolete as they’re replaced by better technologies. If you’re in academia, this might not be a problem, but if you’re in a company that’s trying to turn a profit, this should worry you. Suppose you spend a bunch of money and hire a bunch of researchers and invent a cool new product, only to see it superseded a year later by something even better. That’s how Digital Equipment Corporation must have felt when their cool new “minicomputers” were quickly made obsolete by the advent of the personal computer. It’s Joseph Schumpeter’s “creative destruction” at work.

In Aghion and Howitt’s model, this creative destruction deters companies from investing in research.² It provides a natural brake on the pace of technological innovation, and limits how fast the economy can grow.

In 2005, Aghion and Howitt published an important update to this theory, co-authored with Nick Bloom, Richard Blundell, and Rachel Griffith. The new theory deals with the effect of competition on the rate of innovation. If a market is very competitive, the Aghion and Howitt (1992) theory dominates, and innovation is relatively low. If the market is very uncompetitive, it’s also less innovative, because a monopolist doesn’t feel threatened enough to innovate. But if the market is simply somewhat competitive, then companies will innovate a lot, because whoever wins the competition will get tons of profit from being a temporary monopoly.

Innovation is therefore maximized when companies are “neck and neck”. It’s easy to look at the incredibly expensive AI competition going on right now, and see this kind of “neck and neck” effect at work.

This is all pretty standard macro theory stuff — it imagines a pretty simple economy with just enough complexity to explain the idea that the authors want to think about, and works through the mathematical implications of that theory. And in fact it’s a bit easier to test than many macro theories, because it isn’t actually pure macro — the models’ primary implication is about how individual companies behave, which lets you get some causal evidence.³ Some causal evidence supports the “inverted U” of Aghion et al. (2005), while other studies fail to find it.

What’s harder to think about is how to apply these models. As Lina Khan and other modern antitrust advocates have discovered, there’s not really a big dial labeled “amount of competition in the economy” that you can easily turn. Someday we may be able to do that, but right now, Aghion and Howitt’s most famous theories remain largely descriptive rather than prescriptive.

As a side note, I know Aghion’s research fairly well (Howitt’s less so, sadly), and these aren’t actually my favorite papers of his! He has a 2017 paper with Benjamin Jones and Charles Jones that provides a good way of thinking about how AI will affect economic growth — and pretty prescient, considering it was written five years before ChatGPT even came out. Basically the idea is that AI is still constrained by bottlenecks, and that as AI handles more and more, the bottlenecks become more and more important. This is why Tyler Cowen predicts that AI won’t supercharge growth as much as optimists expect.

Aghion also has a 2018 paper with Bergeaud, Lequien and Melitz, looking at the effects of exports on GDP. As someone who has advocated for export subsidies as a way to boost productivity, I often find myself going back to this paper. The upshot is that top companies become more innovative when they compete (and win) in world markets, but less-competent companies become less innovative due to the creative-destruction effect.

Aghion also isn’t just a theorist; he does important empirical work as well. Aghion et al. (2015) found that China’s industrial policy often increased productivity by boosting competition⁴ — obviously a topic I’m very interested in. His 2023 paper with Blundell and Van Reenen found that regulation has a real and negative effect on businesses in France (though perhaps not as big an effect as one might expect).

And perhaps most relevantly, Aghion, Antonin, Bunel and Jaravel did a literature review in 2022 on the relationship between automation and jobs. They find that at both the company level and the industry level, automation actually increases jobs, probably by growing the overall size of the market:

In this article, we survey the recent literature and discuss two contrasting views on the impacts of automation on labor demand. A first view predicts that firms that automate reduce employment, even if this may ultimately result in job creations taking advantage of the lower equilibrium wage induced by job destructions. A second approach emphasizes the market size and business stealing effects of automation. Automating firms become more productive, which enables them to lower their quality-adjusted prices, and therefore to increase the demand for their products. The resulting increase in scale translates into higher employment by automating firms, potentially at the expense of their competitors through business stealing. Drawing from our empirical work on French firm-level data and a growing literature covering multiple countries, we provide empirical support for this second view: automation has a positive effect on labor demand at the firm level, which remains positive at the industry level as it is not fully offset by business stealing effects. [emphasis mine]

This contradicts the dire predictions of researchers like Daron Acemoglu who believe that automation is a job-killer. It was written before generative AI came out, so this result could change, but it’s highly encouraging.

Anyway, those are my favorite Aghion papers, and I kind of wish more of them would have been cited in his Nobel, but in general I’m very glad he won the prize. He’s really one of the best researchers we have on the topic of innovation — a key voice guiding us through our strange new era of rapid technological change.

Anyway, on to Mokyr. Mokyr’s key work, especially his book A Culture of Growth, is very different than Aghion and Howitt’s. It’s basically a narrative history of the scientific advances that led to the Industrial Revolution. I’ve never read the book, mostly because I’m inherently skeptical of cultural explanations of growth, but I guess now I have to read it.

Mokyr’s explanation of why the Industrial Revolution happened in Early Modern Eu