|

|

|

Explanation: The Comey and James Prosecutions, Dismissed Without Prejudice

Preet's and my conversation and more

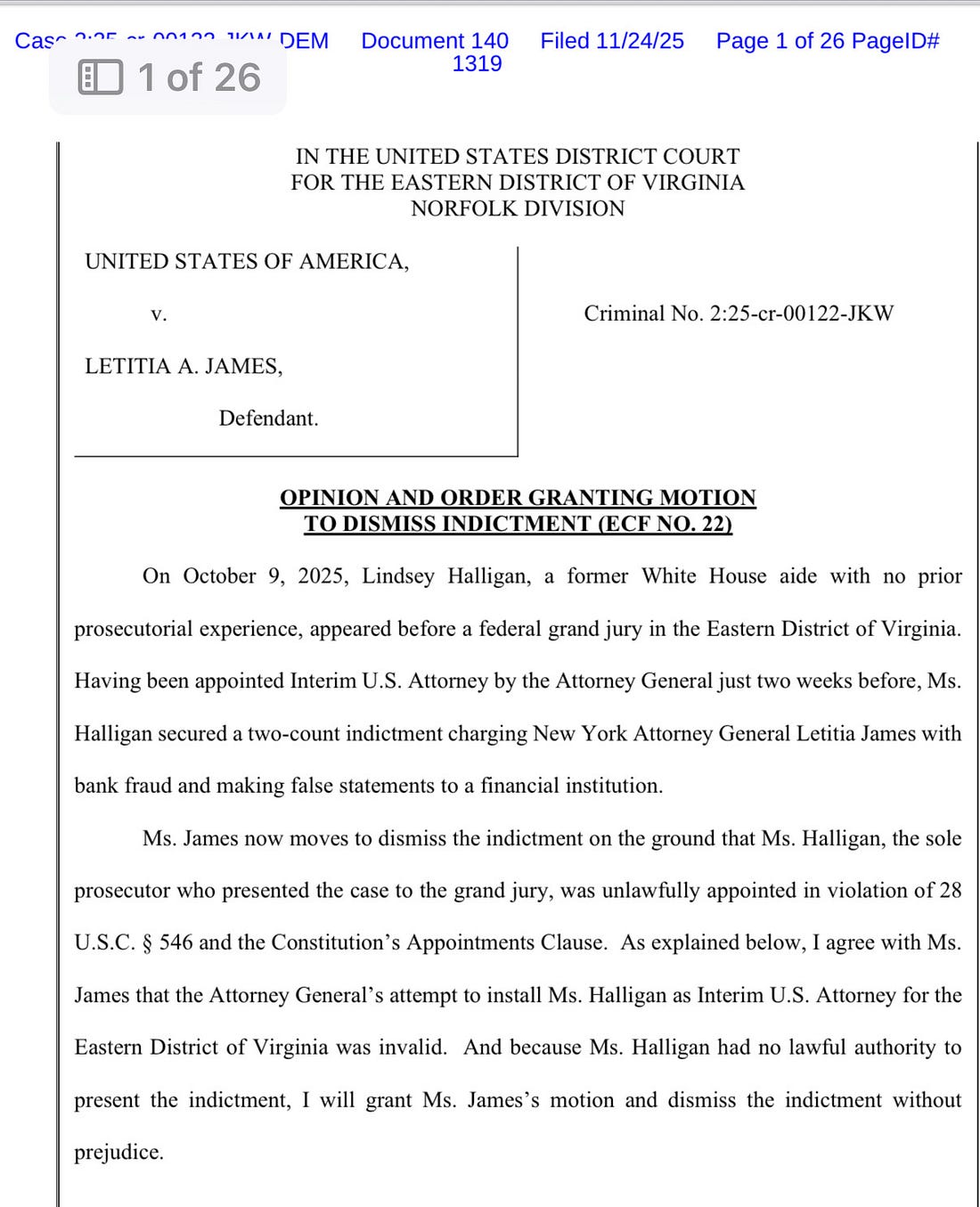

Today, federal District Judge Cameron Currie dismissed the indictments President Trump had ordered his Attorney General Pam Bondi to obtain against people he had decided were his political enemies, former FBI director James Comey and New York Attorney General Letitia James.

Judge Currie ruled that the appointment of Trump’s hand-picked prosecutor, Lindsay Halligan, was invalid. “I conclude that all actions flowing from Ms. Halligan’s defective appointment, including securing and signing Ms. James’s indictment, constitute unlawful exercises of executive power and must be set aside,” she wrote in Letitia James’ case, using similar language to dismiss the Comey prosecution.

My friend and podcast co-host Preet Bharara and I discuss the dismissed indictments and the implications in the video above, which you can watch by clicking. I share some additional thoughts below:

The Constitution requires the president’s nominees to be U.S. Attorneys—there are 93 nationwide at any given time—must be confirmed by the Senate before they can take office. When a presidentially-appointed, Senate-confirmed U.S. Attorney resigns, as frequently happens at the end of an administration, the president can appoint a replacement for 120 days. After that period of time elapses, the local district court appoints an interim U.S. Attorney until a new presidential nominee is confirmed by the Senate and ready to take office. Halligan’s predecessor, Erik Siebert, served out his 120 days. The judges in the Eastern District of Virginia appointed him to continue to serve while his confirmation proceedings were underway. But after Siebert declined to indict Comey because there wasn’t a sufficient basis for doing so, Trump lost confidence in Siebert and said he would fire him. Siebert beat Trump to the jump, resigning before that happened.

The administration’s next move, Judge Currie held today, violated the law. Trump attempted to put Halligan in place, acting as though he could appoint her to another 120-day term in office. Judge Currie pointed out the obvious problem with that approach—if a president could endlessly appoint a new person to a term of 120 days every time the incumbent resigned, the constitutional provision that requires Senate confirmation would be meaningless. That would mean that the check and balance on the power of the executive that the Founding Fathers had put in place would be meaningless. Cronyism could replace competence. That approach, Judge Currie said, violated the law. That meant Lindsay Halligan’s appointment was invalid, and because she had gone alone into the grand jury and her signature was the only one on Comey and James’ indictments, they were invalid. The Judge concluded that based on legal precedent that directed her to restore the defendants to the position they had been in prior to the invalid indictments, she would dismiss without prejudice, which meant that the government was free to (foolishly, given the demonstrated weakness of these cases) indictment the cases again—if the law would allow it.

That, it turns out, is the big question. Will the law allow the two to be indicted again? That question was not before Judge Currie, so she did not decide it. Any future decisions in this regard are likely to center on whether the statute of limitations has run and the period of time the law allots to the government to indict a defendant had expired. The statute in Comey’s case ran days after he was indicted. The calculation in James’ case is unclear, but it too may have or may soon elapse. Although there is a legal provision that can give the government up to six months after a case is dismissed to reindict, here Judge Currie drops a hint in dicta that that may not be the case.

Dicta is what lawyers call remarks made by a judge in a legal opinion that are not essential to the judge’s decision, and while interesting, are not legally binding. Deciding what is and isn’t dicta is one of the challenges law students face when they first study the law. Judge Currie’s comments come in a footnote, which is frequently an indication that what follows is dicta. She was considering Pam Bondi’s attempt to back bless Halligan’s indictment by retroactively conferring special prosecutor status on her, a process that would allow DOJ to wriggle out of the consequences of constitutional violations, but the Judge rejected the argument, along with other attempts at minimization or justification of the error. Then, relying on district court decisions in Maryland and Illinois, Judge Currie wrote that an “invalid indictment ... cannot serve to block the door of limitations as it swings closed,” suggesting, perhaps, that future indictments would not be permitted.

We don’t know for sure how this will come out. The administration is likely to appeal. They have other U.S. Attorneys, like Alina Habba in New Jersey, who are similarly situated, and a concession here could be dangerous. They may, and they seemed to have pledged they would today, also seek new indictments. But Judge Currie has held that Halligan can no longer serve, and unless the government obtains a stay from a higher court, the Judges in the Eastern District of Virginia will appoint the new interim U.S. Attorney, who will remain in place until a new nominee is Senate-confirmed. Given her many errors, it would seem unlikely that Halligan could survive that process. The Court will pick a qualified successor, and based on what we know about the two prosecutions, there is no reason to believe that a new, reasonably qualified U.S. Attorney would differ from Siebert’s assessment that the cases should not be indicted.

A flag here for future appeals—the administration is likely to challenge the law that permits judges to appoint interim U.S. Attorneys, arguing it violates separation of powers by permitting the courts to intrude in the executive branch’s prerogatives. Judge Currie articulated the response in her opinion: Unless the courts are permitted to counterbalance the president in this area, he would be free to make endless appointments free of the scrutiny the Founders put in place. While it will be up to the courts to balance the competing arguments, the need to keep checks and balances in place is a compelling one. With this president and the caliber of some of his choices, the need to do so is even keener.

There was, of course, more news today, including the announced misconduct investigation against Senator Mark Kelly over his participation in a video, along with some of his colleagues in Congress, expressing support for members of the military and intelligence community and affirming their obligation to refuse to follow an illegal order. Kelly is a retired U.S. Navy Captain and NASA astronaut who flew 39 combat missions in Operation Desert Storm and four space shuttle missions as an astronaut. There is absolutely nothing to this—it’s another exercise in revenge. But Kelly could conceivably be returned to duty to face charges; however, based on what we know, military prosecutors would face a difficult task. Members of the military in Article 32 proceedings, the rough equivalent of civilian grand juries, have more rights, including the right to be represented and to question witnesses against them. And everyone in the chain of command must agree on charges before they are brought, which is hard to imagine here. If charges were brought, Kelly would be judged by people of his rank and higher, and it’s difficul