|

|

Can we trust the FBI and this Justice Department after years of watching Donald Trump denigrate and politicize those previously independent agencies? That question was brought into sharp focus by the arrest earlier this week of Brian Cole, Jr., on charges related to planting a pair of pipe bombs outside the headquarters of the Republican and Democratic National Parties in Washington on the eve of January 6, 2021. It’s been almost five years. Did they really get their man all of a sudden?

As we discussed on Thursday, when the arrest was announced, there is nothing wrong with healthy skepticism in this politicized environment. “Trump’s reckless mishandling of the truth, while sometimes used to inveigle people to fall for his lies, ensures that many people don’t believe anything anymore,” I wrote to you. So, how do we decide whether we can believe in these charges, especially in an environment where the Attorney General spent more time criticizing Joe Biden’s administration from the podium than explaining her case? Or when these charges follow the prosecutions of James Comey and Letitia James that were dismissed by a federal judge?

My suggestion on Thursday was that “the best way I know to assess [the validity of the charges against this defendant] is to look at the charges, any evidence DOJ makes available that was used to substantiate them, and the proceedings that will now unfold in court.”

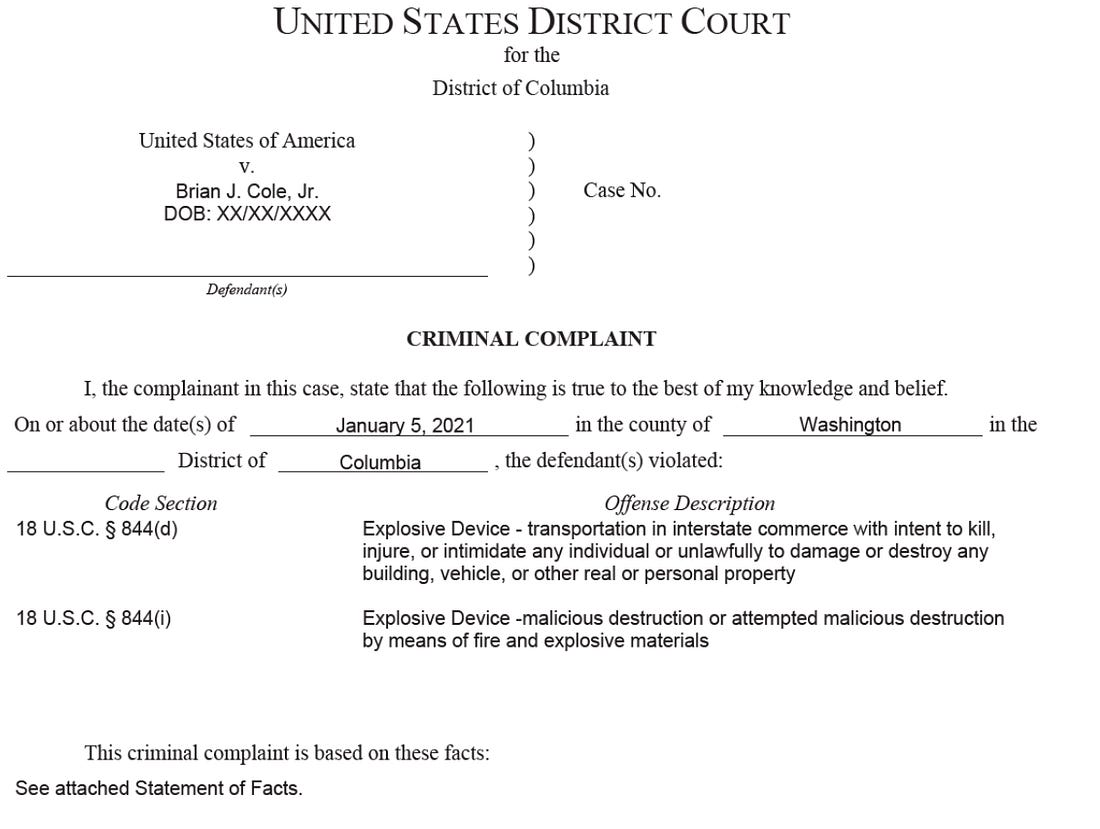

Currently, Cole is charged in a criminal complaint with transporting an explosive device in interstate commerce and attempting to destroy property using an explosive device. The first charge carries a penalty of not more than 20 years in custody, the second, a mandatory minimum penalty of five years, with the total sentence not to exceed 20 years. The charges are serious and it’s possible that, based on evidence obtained as a result of the search of Cole’s home or statements he made to law enforcement, there could be additional charges when the case is indicted before a grand jury, which will happen sometime this month.

But it’s the affidavit accompanying that complaint that gives us the information we will use to assess the prosecution. The affidavit was made under oath by an FBI agent and contains the typical caveat that agents use: It explains that because the affidavit only has to establish probable cause to justify an arrest, “I have not included each and every fact known to me concerning this investigation…only…the facts that I believe are necessary to establish probable cause.” Those facts alone are substantial. If the government can prove what’s in the affidavit—and there’s no reason to believe they can’t, since the information is easily verifiable and an agent has put their career on the line by swearing to these facts under oath—there is every reason to believe the FBI has identified the person responsible for the crime.

The bombs were planted on the evening of January 5 and found on January 6, shortly before the mob breached the Capitol. The affidavit reflects that both IEDs (improvised explosive devices) consisted of an explosive charge in a container. The devices were operational. Importantly for our purposes, the FBI recovered the components of the disrupted devices and traced them–back to Cole.

After tracking a bank account and six credit cards belonging to Cole, agents discovered that he purchased:

Six 1” x 8” galvanized pipes with markings consistent with the manufacturer of the pipe used in the bombs.

12 black end caps and 2 galvanized ones, that are the same brand of end caps used on the pipe bombs. Each bomb had one black and one galvanized end cap.

Five nine-volt batteries that matched the type used in the devices.

Two white kitchen timers of the type used in the devices.

14-gauge red and black electrical wire, which is the type of wire used in the devices, in the same mixture.

Steel wool, which is what the devices were packed with.

Just one of those items alone might not suffice as proof. All of them, together, constitute compelling circumstantial evidence.

The FBI also obtained the phone Cole used and historical cell site records indicating that he was in the immediate vicinity of the RNC and DNC during the relevant time period on January 5, 2021. There were multiple interactions between Cole’s cellphone and cell towers in the relevant area, establishing his presence at the locations at times when the bombs were planted. This is similar to the type of evidence that let law enforcement place the killer of four students in Moscow, Idaho at the scene of that crime. A vehicle that matched Cole’s was observed driving from Virginia, where Cole lives, into the District of Columbia on the evening of January 5.

The FBI also conducted a height analysis based on video surveillance footage that was recovered after the bombs were found. According to the affidavit, “the height analysis showed that the approximate distance from the ground to the top of the individual’s head, including headwear, was 5 feet 7 inches with an error rate of +/- 1.1 inches.” Cole is 5 feet and 6 inches tall.

What’s compelling about the evidence is the way it works together. Cole’s height alone could be a coincidence. But purchases of bomb components, presence in the area where the bombs were planted at the time they were planted, and physical characteristics all taken together become compelling, proof. Much of the evidence contained in the affidavit is circumstantial, which means that it proves a fact indirectly, like finding a suspect’s fingerprints at the scene of a crime, which permits jurors to infer she was present when the crime was committed. Circumstantial evidence permits jurors to draw an inference that the defendant is guilty, as opposed to direct evidence, such as an eyewitness who can testify to the identity of the person who committed a crime because they saw it happen.

Both kinds of evidence are admissible and equally powerful in court, although sometimes people assume, wrongly, that circumstantial evidence is less powerful. This is how judges in my circuit, the Eleventh, instruct juries on the two types of evidence. Other circuits, including the District of Columbia, where this case will be tried, use similar language:

“You shouldn’t be concerned about whether the evidence is direct or circumstantial. ‘Direct evidence’ is the testimony of a person who asserts that he or she has actual knowledge of a fact, such as an eyewitness. ‘Circumstantial evidence’ is proof of a chain of facts and circumstances that tend to prove or disprove a fact. There’s no legal difference in the weight you may give to either direct or circumstantial evidence.”

In other words, it’s up to jurors to decide if the evidence is credible and if they believe it. Circumstantial evidence is just as valuable a direct evidence, so long as it is compelling, when prosecutors argue to juries that the evidence in a case adds up to proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

Cole is innocent until proven guilty. That said, the evidence the government has put forward, in just this initial filing, strongly suggests that this is a case about the evidence and the facts, not some sort of ulterior motive.

At Cole’s initial appearance in court, the prosecutor told the judge that the suspect spoke with the government for more than four hours, but did not reveal the contents of those discussions. There is reporting that Cole confessed to agents after his arrest. A confession is, of course, a key piece of evidence. A defendant can’t be convicted on the strength of a confession alone; there must be a confession plus corroborating evidence. Here, the government appears to have that.

Cole’s motive is still unclear, but the government isn’t required to prove one. There was reporting that Cole told agents he believed the 2020 election was stolen and expressed views supportive of President Donald Trump. But how that plays into his alleged crimes hasn’t been made public.