|

I invite you to upgrade to a paid subscription. Paid subscribers have told me they have appreciated my thoughts & ideas in the past & would like to see more of them in the future. In addition, paid subscribers form their own community of folks investing in improving software design—theirs, their colleagues, & their profession.

You’re typing. You pause. You wait. And wait. The little spinner spins. Your mind wanders. What was I doing again?

Back in 1982, Walter Doherty and Ahrvind Thadani at IBM published research that challenged the prevailing wisdom. Everyone assumed 2 seconds was an acceptable response time for computer systems. Doherty and Thadani said no—400 milliseconds is where the magic happens. Below that threshold, users stay engaged. Above it, they start drifting into a “waiting” state.

This became known as the Doherty Threshold, and it fits neatly inside Jakob Nielsen’s broader response-time framework: 0.1 seconds feels instantaneous, 1 second keeps your flow of thought but you notice the delay, 10 seconds risks losing you entirely. The 400ms mark is where “continuous” starts degrading into “merely acceptable.”

No research says “human attention starts to slip at exactly 400 milliseconds.” The number is a practically motivated threshold, not a universal cognitive constant. But the IBM productivity research was real. The perceptual bands are real. And anyone who’s waited for a build to finish knows the phenomenon is real, even if the exact boundary is fuzzy.

400 milliseconds. That’s the window. Give or take.

The Tradeoff Nobody Talks About

Modern IDEs/languages/tools have made a choice, and not consciously—choosing completeness over speed. VSCode wants to tell you everything that’s wrong with your code—every type error, every lint warning, every possible issue. And it will take as long as necessary to give you the whole picture.

The extreme version of this philosophy is theorem provers. “We will give you perfect feedback about your code. We will prove it correct. It will just take... a while.”

I’m not saying theorem provers are bad. I’m having fun working with Lean (with a genie’s help). Theorem proving is valuable for certain problems. But it’s at the far end of a spectrum:

Fast but incomplete ←————————————→ Complete but slowMost IDEs have drifted toward the right side of this spectrum without acknowledging the cost. Every millisecond over 400 is attention tax. Every second of delay is an invitation for your mind to wander off and check email. What if we just didn’t?

What Are We Optimizing For?

What is feedback for?

Did I do what I think I just did?

Did I break anything in the process?

Quick feedback keeps you in flow. Did that work? Yes? Next.

What if I could learn about most of my errors in 400 milliseconds rather than all of my errors in 30 seconds? The first keeps me in the zone. The second kicks me out of it.

It’s as if IDEs/languages/tools operate with this implicit assumption:

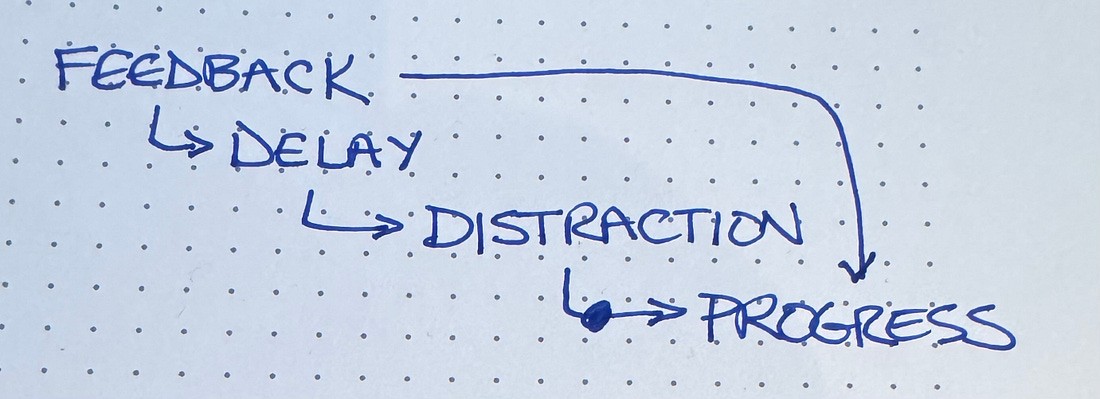

More feedback leads to more progress. That’s part of the story but there’s more:

Which of these effects is stronger?

When something breaks in production, the first question isn’t “tell me everything.” It’s “what changed?”—and the answer needs to arrive before you context-switch.

Early-signal systems should be designed to surface the most important change fast, so you can stay in flow and decide what to do next. Instead of waiting on perfect answers, you get fast, close-to-right insight that keeps investigations moving forward.

Read the blog, “Fast and Close to Right: How Accurate Should AI Agents Be?” to learn why speed, partial answers, and early signals matter more than completeness, and how Honeycomb designs for fast understanding in observability.

This post is sponsored by Honeycomb.

The Old Tools Knew Something

There’s a reason programmers my age get nostalgic about certain tools from our past, the LISP machines, the Smalltalks. They were fast. Blazingly, impossibly fast by modern standards. They often gave you feedback as soon as your finger left the key.

Yes, they missed things. Yes, modern tools catch more errors. But those old tools respected human attention, the 400 milliseconds.

Somewhere along the way, we decided that more feedback was always better feedback. We forgot that feedback has a time dimension, not just a completeness dimension.

What Would Better Look Like?

I don’t have a complete answer, but I have some principles:

Prioritize ruthlessly. Not all feedback is equally valuable. Show me the most important thing first, fast. The rest can come later. Tests that have failed recently are more likely to fail than tests that have run flawlessly for years. Run them first.

Degrade gracefully. If you can’t give me complete feedback in 400ms, give me something. A partial result is better than a spinner.

Let me choose. Minute-by-minute I want some feedback now. On my espresso break I’d like more reassurance. Let me make that tradeoff consciously.