|

|

I was writing a post about the economics of AI, but my elderly disabled pet rabbit had a bit of a health emergency, so the AI post will have to wait until tomorrow. In the meantime, I know you’d like something to read in the morning, so here’s a repost from a few years back.

The big news out of China this past week wasn’t about electric cars or semiconductors or real estate. It was about Xi Jinping purging his top general (and close friend) Zhang Youxia, along with another top general named Liu Zhenli. No one knows exactly why this happened — I speculated about a coup plot in my weekly roundup, but most analysts don’t talk about that possibility. Here are three analyses that I found pretty interesting:

Jon Czin (interviewed by Jordan Schneider) thinks Xi probably purged Zhang out of pure paranoia — Zhang was powerful and had a lot of people loyal to him, and Xi may have simply been afraid that Zhang could turn into a rival.

Youlun Nie thinks Zhang simply wasn’t doing a good job getting the Chinese military ready for an invasion of Taiwan (and that this fact had been exposed by Zhang’s rivals, who were purged earlier). Xi may have simply decided to clean house and start afresh.

K. Tristan Tang thinks Zhang simply didn’t want to get ready to invade Taiwan so quickly, and that Xi removed Zhang for resisting his orders.

In the end we can’t really know. But it opens up the possibility that Xi is entering his “lion in winter” phase. Xi isn’t an organization-builder, like Mao, Lenin, Elon Musk, etc. He’s an organization-dominator, like Stalin — a guy who rises through the ranks of a big existing power structure by being very good at patronage, backstabbing, and various other power games.

Guys like this are always incredibly paranoid, because they had to be in order to reach the top. And as they age and start to slow down, they often get even more paranoid that they’re about to be overthrown — both because they’re a weaker target, and because everyone starts fighting over the succession. At 72, Xi is already several years older than Joseph Stalin was when he descended into his terminal paranoia.

The rest of the world may thus catch a break. Xi has no term limits and no obvious successor, meaning he will probably be in power for another decade and a half unless he’s forcibly overthrown or dies prematurely of natural causes. During that time, he may be more and more focused on fighting off (real or perceived) internal challengers. This could divert his attention from attacking Taiwan, Japan, the United States, India, etc. By the time Xi is replaced in the late 2030s or 2040s, demographic decline and societal disruptions from AI may have set in, a more reasonable post-Xi leadership may decide that launching World War III is pointless.

This will not be fun for China, because internal strife at the top would tend to make policy more rudderless, and occasionally even predatory. But I bet that China’s companies, local governments, and people would be competent and clever enough to limit the damage from the top.

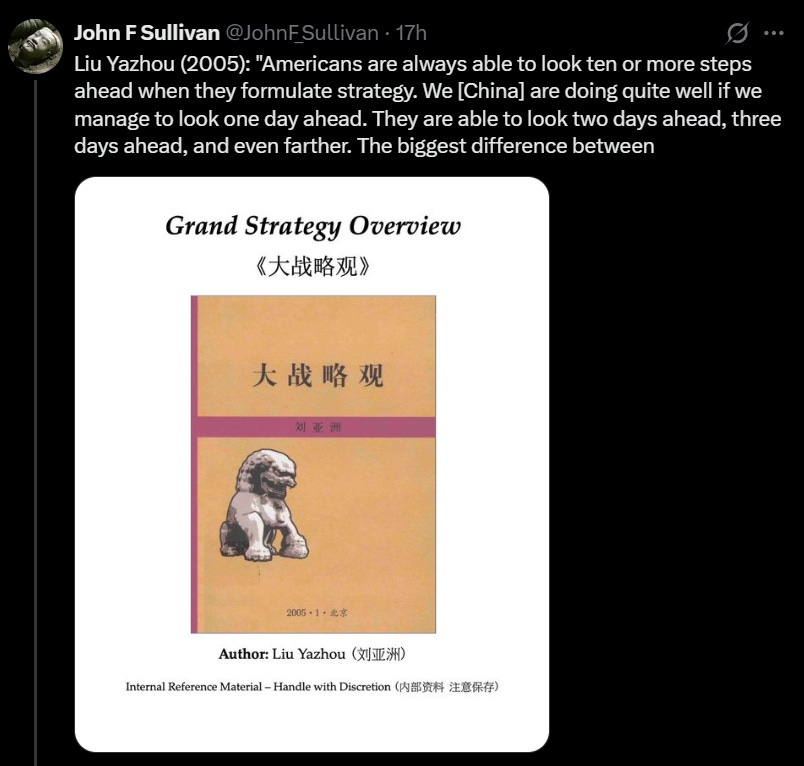

Anyway, this round of purges should emphasize that China doesn’t really fit the stereotypes that many Westerners apply to it. In particular, the common notion that China is a patient, far-sighted entity — as compared with the impulsive, short-sighted West — seems obviously wrong. Here’s what a Chinese writer said in 2005:

In 2022, I wrote a post about this stereotype, and argued that it was nonsense. Here is that post:

As part of my China reading series, I’m now reading Graham Allison’s Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’ Trap?, which is about the possibility of the U.S. and China stumbling into war. Though the warning is timely and useful, Destined for War has a section about cultural differences that’s both atrocious and entirely out of place in the rest of the book. It relies on many of the same tics and stereotypes as Michael Pillsbury’s The Hundred-Year Marathon — for example, alleging that Chinese people still think in terms of metaphors from the Warring States period 2300 years ago.

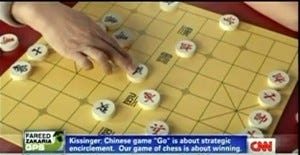

One particularly silly example Allison repeats is the idea that Chinese people think about strategy in terms of the game Go (weiqi in Chinese), while Americans think in terms of chess. The metaphor, apparently, is that China thinks in terms of strategic encirclement while Americans try to checkmate the opponent. This analogy actually comes from Henry Kissinger, who helped establish a de facto alliance between the two countries during the Cold War, and wrote a whole book about China that people still quote lovingly to this day. Kissinger reiterated the metaphor in a 2011 interview on CNN, which featured the following image:

But as some of you may have noticed, the game pictured is not Go. It’s xiangqi, also known as “Chinese chess”. Xiangqi is similar to chess (the goal is to checkmate your opponent), but it’s faster-paced and more tactical, with more open space on the board. Games tend to be faster than chess games. And in China, xiangqi is much more popular than Go. So even if the idea of analyzing country’s strategic cultures based on popular board games made any sense whatsoever (which it does not), if we looked at xiangqi we might conclude that Chinese strategic culture is like America’s, but faster-paced and more aggressive.

In other words, assuming Kissinger was not just a complete doofus, he chose this metaphor based not on how accurately it describes Chinese thinking, but on how he wanted Americans to think about responding to China. And in fact, U.S. policy to balance China has been based on encirclement, much to Chinese leaders’ annoyance. Kissinger successfully got the U.S. to “play Go”.