|

I came across a story the other day proving that analysts don't always have their incentives aligned with yours.

In 1998, Henry Blodget, a CNN business-news intern made a name for himself with a bold call on Amazon.com.

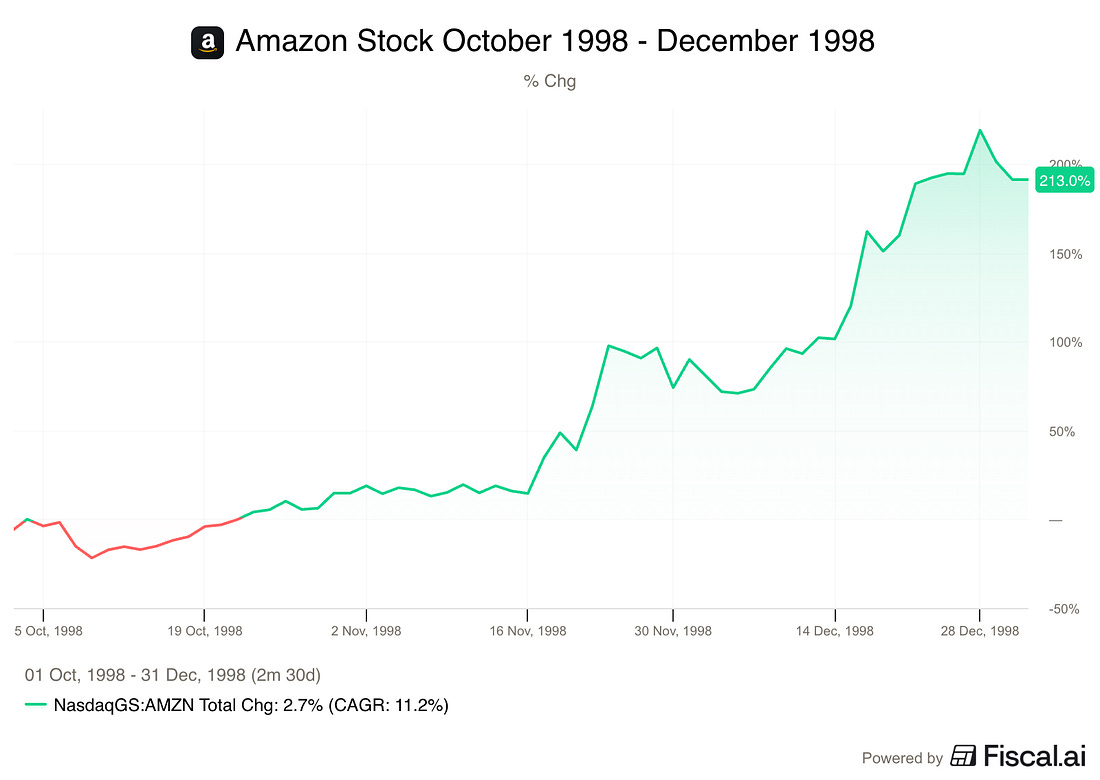

He predicted that Amazon’s shares would double within a year.

This was considered very unlikely.

It only took 3 weeks for Blodget to be proven right.

He became an instant Wall Street celebrity, and looked like a genius.

By December of 1998, Amazon’s stock had doubled again.

|

Right Too Early

At the same time Blodget made his call, Merrill Lynch’s internet analyst, Jonathan Cohen, was convinced that Amazon’s shares would fall.

Cohen was fired, and Blodget was hired with one of the highest salaries for an internet analyst.

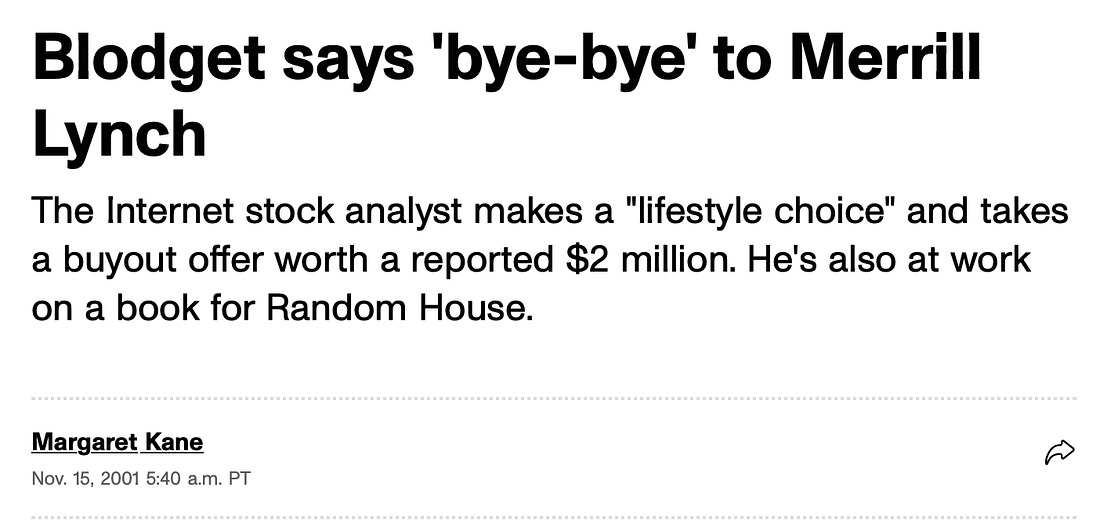

By 2001, Blogdet had accepted a buyout offer from Merrill and left the firm.

Blodget’s Scandal

In 2002, New York’s Attorney General published private emails in which Blogdet called stocks he was publicly recommending ‘garbage’, and much worse.

If you’re familiar with the acronym POS, you get the idea.

In 2003 he was charged with civil securities fraud, paid a $4 million fine and received a lifetime ban from the SEC.

There’s a few things we can take away from this.

Both Were Right

The first and most obvious being that analysts have incentives that have nothing to do with getting their assessment of a company right.

The second being that analysts can be right for the wrong reasons, or just lucky.

But a less obvious thing that I took away is that both analysts turned out to be right.

It just depends on what timeframe you’re looking at.

Blodget was right in the short term. Amazon’s stock had a ton of momentum, hit his price target, then doubled again, all within a year.

But by the end of 2000, Jonathan Cohen was proven right, with Amazon down 9% from where it started October of 1998.

|

By the end of 2001, Amazon stock had seen a drawdown of more than 90%.