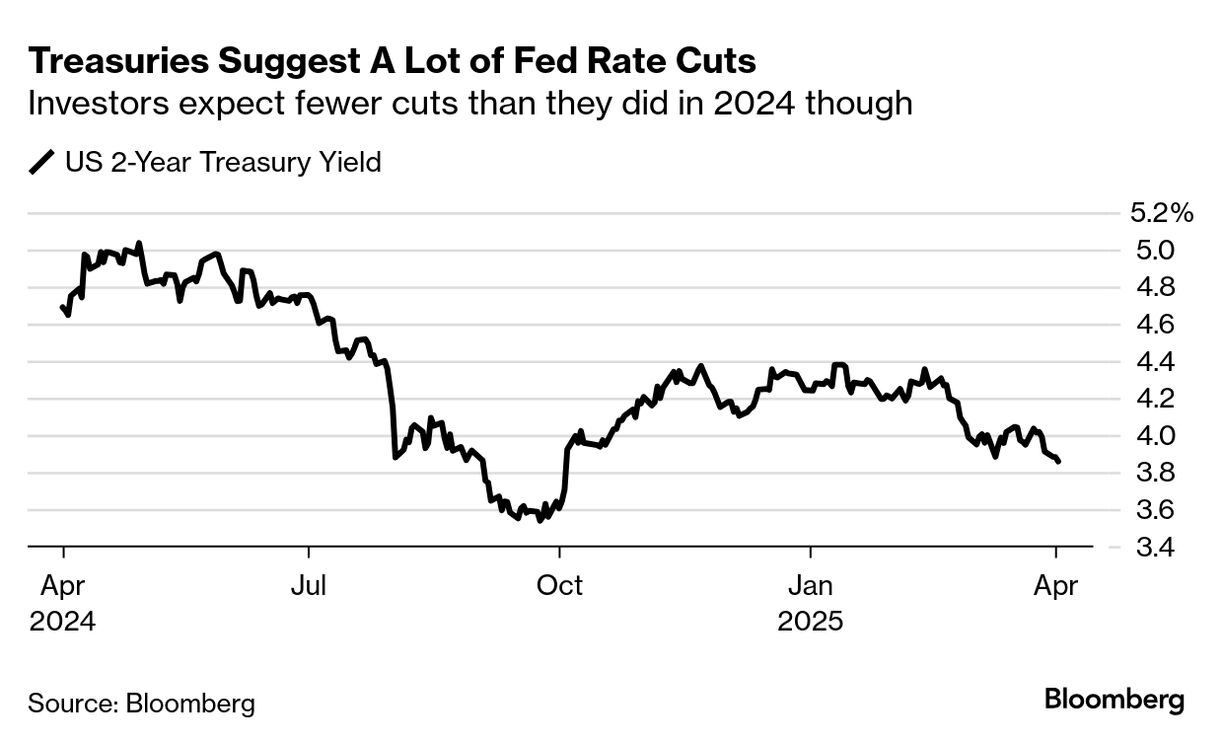

| If you want to get a sense of what the bond market is saying about the US economy, look at the two-year Treasury yield. That’s because most economic events that draw a monetary policy response from the Federal Reserve which bond investors can price are packed into that time period.  By that metric, investors have been through some wild shifts in sentiment over the past year. They started last spring convinced the Fed was going to hold the line on the fed funds rate for the indefinite future, only to see those bets crumble as the US economic data deteriorated into a potential recession. The Fed’s outsized half-point rate cut in September turned things around, though. The two-year yield then vaulted higher to signify increasing confidence in the economy (with a hint of inflation worries, too). But as the Trump economic agenda took hold from January forward, we’ve seen yields plummet again despite inflation worries. Right now the two-year yield is about 30 basis points lower than it was on election night in November. The yield isn’t as low as it was during last year’s recession scare. And a lot of that owes to worries about stagflation. We can see those worries via the difference between the two-year yield and the yield of the equivalent inflation-protected securities (TIPS). Fed cuts certainly eased recession fears. But they also stoked inflation fears that have become even more pronounced with tariffs looming. The breakeven between normal Treasuries and TIPS is around 3.30% now, which tells you the bond market thinks inflation is going to go accelerate. To give you a sense of the angst here, the last time expected inflation over the next two years was as high as it is today, the then-current inflation rate was about 5%. So bond investors appear to be terrified of tariffs because of inflation, which erodes the value of bonds. But investors also think the economy will slow so much that the Fed has to cut rates. Three rate cuts are priced in for 2024 alone, according to the swaps market and fed fund futures. Are bond investors predicting a recession? It’s hard to say. At a minimum, it screams stagflation — slowing growth and rising inflation. Stocks want none of this stagflation stuff | On the equities side of the ledger, I did an analysis of the 1960s for terminal clients at the beginning of the week (terminal link here). One of the key takeaways from that “stagflation-lite” period is that even moderately high levels of inflation are bad for equity investors. From the beginning of 1966 to the end of 1969, the consumer price index increased by 18.4% in total or 4.3% annually. And the S&P 500 was barely changed. Basically, you lost almost 20% in real terms. Equity investors want nothing to do with “stagflation lite,” if that’s what tariffs entail. And you can see equities already pricing in this possibility, given the steep declines in in March from recent all-time highs that briefly sent the S&P 500 Index into correction territory. Still, the market has retraced some of those losses. And despite a 20% decline in the Mag 7 market leaders, investors haven’t given up on equities as much as they have taken profits and re-allocated some of their investments to more defensive sectors such as health care and consumer staples. For example, the iShares US Consumer Staples ETF (IYK) has gained more than 1% in the last month and nearly 10% over the last three months. So stocks are saying, “Yes, the economy is slowing and inflation will stay a bit elevated. But we think we avoid a recession. Inflation-resistant stocks are going to ride this tariff stuff out.” |