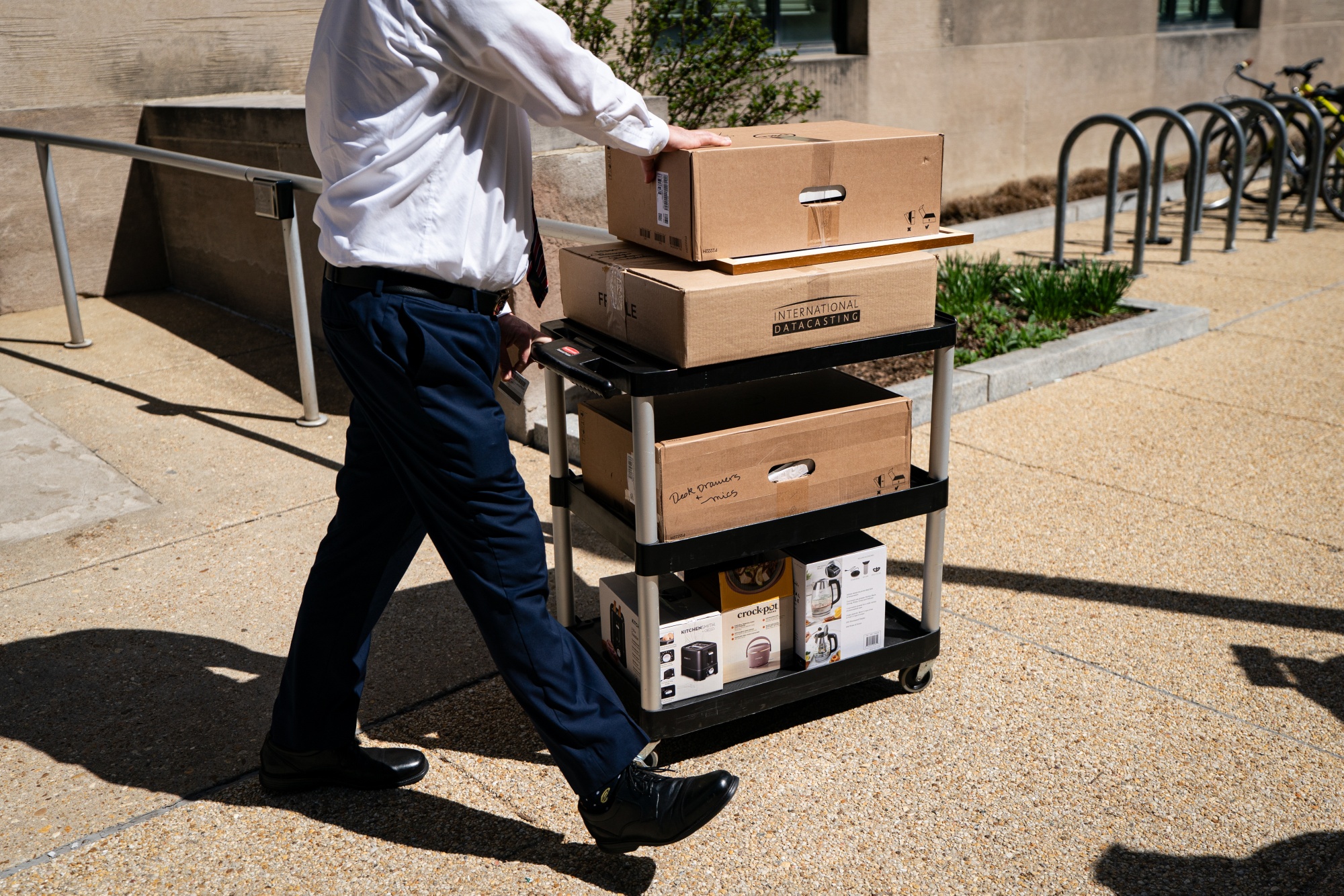

| By Brian Kahn US President Donald Trump’s tariffs are rippling around the world like a boulder dropped in a pond. He announced on Wednesday blanket tariffs of at least 10% on all countries, with many seeing rates that are much higher. The exact impacts on the energy transition will take days if not weeks to tease out. But there are some indications of what the tariffs will mean in the US and for the rest of the world. To pick up the signal through the noise, I spoke with BloombergNEF’s head of supply chains and trade Antoine Vagneur-Jones. Here are a few takeaways. China will export more clean tech — to low- and middle-income countries. China faces a stiff penalty with Trump’s new tariffs of 34%, which comes on top of a 20% hike earlier this year. And that comes on top of tariffs former President Joe Biden leveled on Chinese solar panels last year. The country also faces surcharges on other carbon-cutting products like electric vehicles and batteries. Soon after Trump’s announcement in the White House Rose Garden, Vagneur-Jones said in a WhatsApp message that the tariffs “will speed up a recent trend of China exporting more to middle and lower income countries.” From 2022 to 2024, the share of Chinese exports of EVs, wind turbines, solar panels and lithium-ion batteries to those countries rose rapidly, according to BNEF. Solar panels will be caught up in the trade war. The tariff rates for “several Southeast Asian countries” are “pretty devastating,” Vagneur-Jones said. That’s also where most US solar imports come from, with Vietnam being a top supplier. The country was hit with a 46% tariff while Cambodia and Thailand — also notable exporters — saw surcharges of 49% and 36% respectively. The US imports vastly more panels than it makes. India stands to benefit. The country got off relatively light compared to China and Southeast Asia, with a tariff rate of 26%. That comes as it ramps up clean tech manufacturing capacity, including recently working to finalize a $1 billion subsidy to grow the solar industry. India increased its solar exports to the US in the past two years, with 9.4 gigawatts of cells and modules from the market, worth $3.4 billion, reaching the US in 2023 and 2024 combined, according to customs data. This compares with very low levels in previous years. With higher tariffs on Vietnamese and other panels, India may have an opening. “The lower duties could potentially boost future exports,” Vagneur-Jones said. But ultimately nobody wins. The world needs to speed up the energy transition to avert the worst impacts of climate change, not throw up hurdles. But the tariffs are essentially throwing up entire walls that will impact all industries, particularly those that rely on supply chains going back to China and other countries. (Which is to say nearly all industries.) While the tariffs in theory are designed to bolster US manufacturing, “extreme volatility puts firms off putting money down for assets with a 20-year depreciation timeline, and inflating the cost of inputs makes scaling manufacturing considerably harder,” Vagneur-Jones said. Want to know more? Bloomberg Green has already looked at what the US’s trade war could mean for key components of the energy transition — from electric vehicles to heat pumps and even New York’s green power supplies. Keep up with the latest news on Bloomberg.com. This climate health cut might hurt a bit | By Zahra Hirji A team of federal officials tasked with helping cities and states navigate the effects of climate change on people’s health was disbanded Tuesday, part of a sweeping overhaul ordered by US Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. More than a dozen staffers comprising the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s climate health program were among the thousands of workers at the Department of Health and Human Services who received dismissal notices. The climate health program was part of the CDC’s Division of Environmental Health and Science Practice, which employed hundreds of people who worked on everything from asthma to lead poisoning prevention. All of those positions were cut as well. “These are people who have been doing exceptional work and gotten excellent performance reviews, but now they’re not there to help protect the health of people in places like Flint, Michigan,” said Paul Schramm, the climate program’s chief until he too was put on administrative leave on Tuesday. “There’s no one in the federal government doing that anymore.”  A worker wheels out the belongings of a fellow employee who was dismissed outside of the Mary E. Switzer Federal Office Building, which houses offices for the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), in Washington, DC, on Tuesday, April 1, 2025. Photographer: Al Drago/Bloomberg Schramm’s unit provided more than $4 million in grants to help local and state officials identify and respond to climate change and associated health problems. The loss of this funding leaves communities vulnerable at a time when health departments around the country are “already severely understaffed and severely underfunded,” said Schramm, who has worked at CDC for 16 years. Schramm spoke with Bloomberg News about what the cuts to the climate health program mean for the communities it served. HHS did not respond to a request for comment. This interview has been edited for clarity and length. How did you find out about the layoffs? I woke up early. Everyone’s been having trouble sleeping because of all this. So I got a text around 6 a.m. from one of the staff on my team saying they received a reduction-in-force notice. Then I got another text and then I checked [my email] and I had one. It became clear very quickly that our entire climate health program had received an email saying that [we] will be terminated due to reduction in force. Then we found out it was all of our division. [Schramm says he was told he was on administrative leave, effective immediately, until his last day on June 2.] What type of work did the climate health program do, and what happens now that it’s been abruptly halted? Communities and health departments around the country are no longer receiving funding and support to protect people from things like heat waves, flooding, wildfires, drought. Most of the time, a state doesn’t have their own resources or hasn’t allocated resources to come up with a heat-wave plan or open a system of cooling centers statewide, or even to have a communication plan to help get the message out on what you should do on particularly hot days. What we did was provide them with a framework to do that and to set up a program to implement these activities on the ground. What were you working on that may not get completed? There’s not a federal system to monitor pollen, but there are some private systems. We’ve been working for a long time to come up with data use agreements to make that data available to the public for people who have severe allergies and also for researchers. We were getting ready to put that up on our portals. I don’t see how that can happen now. What does pollen data have to do with climate change? We’ve done research on why pollen amounts are increasing and why pollen or allergy season is starting earlier in the year. We’ve shown that is tied to things like temperature and precipitation. And in many parts of the country, we’re getting more pollen than we’ve ever seen. In fact, right here in Atlanta, where there’s a monitor that’s been measuring [pollen] for 35 years, we set the all-time record on Saturday. And then we set the second-highest record on Sunday. It’s really important for researchers to have that data so they can continue to look into this, to find ways to protect people’s health and to both monitor the pollen and to model when pollen season is shifting so that people who need allergy shots or medication can do it [earlier] — because it’s earlier in the year than it’s ever been before. Now we won’t be here to do that. How do you feel about it all? Right now, I am mostly sad. It’s disappointing. I’ve worked with people, not just here at the CDC, but all of the hundreds of people I’ve collaborated with in local health departments and nonprofits, who see what a big problem that this is — how climate change is impacting health. We’ve got the data. We’ve seen it in action. We know about the thousands of people who die from heat each year. We know about the more than 100,000 who have to go to emergency rooms for heat. One of the things that’s really kept me going and so passionate about this is that there’s such a broad network of people working on this. What I’m feeling right now is sad that the heart of that is being ripped out and the loss of expertise, the loss of funding — it’s going to hurt communities. Read the full story on Bloomberg.com. |