| I do not want to write about the tariffs, because there is a pretty overwhelming consensus that they are bad, and that consensus strikes me as correct, so what can I add? “Trump Tariffs Wipe Out $2 Trillion From US Stock Market,” reports Bloomberg. “Wall Street analysts anguish over ‘Liberation Day,’” reports FT Alphaville. “You Can NOT Be Serious!,” writes my Bloomberg Opinion colleague John Authers. Perhaps there is something interesting about the “reciprocal” tariff formula, which notionally tariffs countries based on the “unfair tariff disparities and non-tariff barriers” that they impose on US goods, but which actually tariffs countries based on their trade surplus with the US. Bloomberg’s Josh Wingrove reports: In a statement published Wednesday night to explain its methodology for tariffs that rocked the globe, the United States Trade Representative detailed a formula that divides a country’s trade surplus with the US by its total exports, based on data from the US Census Bureau for 2024. And then that number was divided by two, producing the “discounted” rate. China, for instance, had a trade surplus of $295 billion with the US last year on total exports of $438 billion — a ratio of 68%. Divided by two according to Trump’s formula, that yielded a tariff rate of 34%. Two related points here. [1] One is the quite explicit assumption — from the USTR statement — “that persistent trade deficits are due to a combination of tariff and non-tariff factors that prevent trade from balancing.” That is, if a country exports more goods to the US than it imports from the US, that is necessarily unfair, and if you can’t find a tariff that explains the disparity, you can simply assume a secret mystery tariff: While individually computing the trade deficit effects of tens of thousands of tariff, regulatory, tax and other policies in each country is complex, if not impossible, their combined effects can be proxied by computing the tariff level consistent with driving bilateral trade deficits to zero. If trade deficits are persistent because of tariff and non-tariff policies and fundamentals, then the tariff rate consistent with offsetting these policies and fundamentals is reciprocal and fair.

I guess the word “fundamentals” appears there: A country could export more goods to the US than it imports from the US for fundamental reasons, not just tariffs and non-tariff protectionist policies. But “offsetting the fundamentals” is also “reciprocal and fair.” So for instance you could crudely characterize a portion of the trade between Vietnam and the US as (1) Vietnamese wages are lower than US wages, so Vietnamese people make sneakers and t-shirts that they sell to the US cheaply for dollars and (2) the US financial system is big, so Vietnamese people invest those dollars in US financial assets. We are good at making financial assets, they are good at making low-cost clothing, so we trade. To Trump this is necessarily unfair and we must stop it. My Bloomberg colleague Joe Weisenthal writes: Now we’re slapping massive tariffs on them, but the question is ... to what end? Do we think there are hundreds of thousands of people in the US eager to work in sneaker and t-shirt factories at the wages that sneaker and t-shirt factories pay? Are there people eager to work in sneaker factories even at ‘good’ wages? Do we think that the US has the level of robotic capability to replace these factories without having to hire a lot of workers? And if not, what is the administration trying to accomplish?

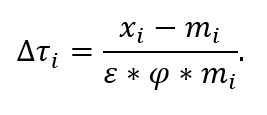

Now my biases are obvious: I am a financial columnist because I find finance delightful, and a world in which the US gives people finance and gets back inexpensive goods strikes me as good for the US. We give them entries in computer databases, they give us back food and clothing: That is a magical deal for us! Clearly people disagree, and I suppose some of that disagreement is plausible, but I also think that Weisenthal is right about the sneaker factories. The second point I would make here is that, if you read the USTR statement, it actually prints a formula. Bloomberg reports that it is “a formula that divides a country’s trade surplus with the US by its total exports.” The country’s surplus is its exports minus its imports, so the formula can be rewritten “Tariff = (exports to US - imports from US) divided by (exports to US),” or in symbols: Where tau is the “correct” tariff rate, m is US imports from the country (its exports to the US) and x is US exports to the country (its imports from the US). And then you “discount” the correct rate by 50% to get the Trump tariffs. The USTR does not print that formula. It prints this one:  Source: Office of the United States Trade Representative Don’t worry about the delta in front of the tau, or the subscript i’s; those are just decoration. [2] More substantively, the USTR has added an epsilon and a phi to the denominator of the equation. What do those parameters represent? Well, epsilon represents “negative 4,” and phi represents “0.25.” If you multiply them together you get negative 1. So it’s the same equation as I wrote — surplus divided by exports — but with some extra Greek letters. [3] Why did the USTR write a minus sign as “epsilon times phi”? Well, there is an explanation. Epsilon is “the elasticity of imports with respect to import price,” phi is “the passthrough from tariffs to import price,” and they happen to exactly offset: A 1% increase in tariffs increases import prices by 0.25%, which reduces import demand by 1%. So a tariff equal (in percentage terms) to the country’s trade surplus with the US will exactly eliminate that surplus. The USTR cites some studies not finding those results, [4] and then makes up numbers for convenient arithmetic. But exactly eliminating the country’s trade surplus (the US trade deficit) is the stated goal. The Financial Times reports: Oleksandr Shepotylo, an econometrician at Aston University, Birmingham, which recently modelled the effects of a global trade war, said the use of economic formulas merely gave the USTR document “a sense of being linked to economic theory”, but it was in fact divorced from the reality of trade economics. “The formula . . . gives you a level of tariff that would reduce [the] bilateral trade deficit to zero. This is an insane objective. There is no economic reason to have balanced trade with all countries,” he said. “So in this sense, this policy is very unorthodox and cannot be defended at all.”

Well, yes. I just like that they made up the numbers to get an exact negative 1. Again, I am a financial columnist, and I have a patriotic appreciation for the US’s export industry of finance, and two of that industry’s most popular products are: - Sprinkling some Greek letters on your work to add visual interest, and

- Making up parameters to solve for the result you want.

Even in this tariff announcement, you see the US leaning into its comparative advantage. Yesterday Donald Trump unilaterally imposed big tariffs due to his own idiosyncratic understanding of economics. But why does he get to do that? The US Constitution says that “the Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises.” Congress, not the president, gets to set tariffs. Over the years, though, Congress has mostly handed that power over in a series of laws delegating tariff authority to the president. Yesterday’s tariff announcement relies on one of those laws, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977, which allows the president to declare a “national emergency” due to “an unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States” and respond to that emergency in various ways including by regulating or prohibiting imports. “No president had used IEEPA to impose tariffs until this year,” notes the Congressional Research Service in a useful report, but now Trump has “declared that foreign trade and economic practices” — all of them — “have created a national emergency” allowing him to make up whatever tariffs he wants. The law also allows Congress to reverse the president’s actions, and in fact the US Senate already voted to block some of Trump’s previous tariffs on Canada, though the House of Representatives is unlikely to vote on the measure. You could imagine that changing in response to the latest round of blanket tariffs, but you’d have to work pretty hard to imagine it. One other thing that I think about, though, is the “nondelegation doctrine.” This is an old legal theory that Congress cannot hand over its legislative power to the executive branch: Executive agencies can interpret and carry out the law, but they can’t make law; an act of Congress saying “the Securities and Exchange Commission should just decide what the rules are for crypto” is arguably an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to the executive branch. At the very least, Congress has to set the general policy and give the SEC guidance about what the rules should do; the SEC can’t just do whatever it wants. This theory has, for nearly a century, been pretty dead: The Supreme Court has rejected pretty much every modern nondelegation-doctrine challenge to agency rulemaking, and in fact the CRS notes that “Supreme Court decisions upholding tariff laws have become landmarks in the development of a broader ‘nondelegation doctrine’ concerning the extent to which Congress may lawfully delegate authority to the executive branch.” But, as we have discussed a couple of times in the SEC context, that might be changing: US courts, including the Supreme Court, are increasingly interested in reviving the nondelegation doctrine. The IEEPA — as interpreted in the Trump tariffs anyway — is an exceptionally broad delegation of powers: Only Congress has the constitutional power to impose tariffs, but apparently in the IEEPA it gave the president power to impose any tariffs he wants with no guidance or limits. Seems like an interesting nondelegation case? It is plausible that the current state of US constitutional law is “administrative agencies can’t make securities regulations or environmental rules, but of course Donald Trump can do whatever tariffs he wants.” But it’s not necessarily true. Some importer should bring a nondelegation case! Could be fun! (Disclosure-brag: As I’ve mentioned before, my wife has argued a nondelegation case in the Supreme Court, so I have a certain personal connection to this frankly pretty speculative theory.) The stock market is crashing today because Trump announced tariffs that were much bigger than the market anticipated. Meanwhile financial traders were setting themselves up for the only tariffs that didn’t happen: A massive arbitrage trade that has drawn tens of billions of dollars’ worth of gold and silver to the US came to an abrupt halt with Wednesday’s announcement that precious metals would be exempt from Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs. For several months, prices in New York have traded at large and unusual premiums to global benchmarks as traders weighed the risk that precious metals could be caught up in tariffs. The differential created an incentive for banks and traders to load planes and ships with so much bullion that it distorted US trade data in the process. On Thursday, US premiums for precious metals tumbled after a list of exemptions from the tariffs included gold, silver, platinum and palladium. … “Yesterday’s announcement effectively puts an end to the massive flow of precious metals into the US over the last few months as the EFPs collapse,” said Anant Jatia, chief investment officer at Greenland Investment Management, a hedge fund specializing in commodity arbitrage trading. We talked about this “arbitrage” in February and again in March, when I pointed out that a commodity in the US is no longer economically equivalent to the same commodity outside of the US, “nor is it equivalent to, like, ‘the same commodity plus 25%,’ because the tariffs are uncertain.” Gold in New York was worth (1) the value of gold in London plus (2) some premium representing the expected value of possible future tariffs on importing gold into the US. That expectation was high, and now it is lower, but to be fair you never know what will happen tomorrow. People are worried about stock buybacks | I mean, if you don’t like stock buybacks, I guess tariffs did solve that problem: US companies last month announced the fewest stock buybacks, in dollar terms, since the Covid pandemic, an early sign of cash hoarding from worries about economic growth and the impact of a global trade war. ... “No one knows what will happen with tariffs,” said Jeffrey Yale Rubin, president of Birinyi Associates. “So how are corporate executives supposed to plan for cash flows? It’s a lot easier to slow buybacks than cut dividends until companies know more about the trade outlook.” Again, my bias is that exchanging financial creativity for goods and services is mostly a good thing for the US, but clearly the Trump theory is that that’s wrong. I don’t think that this means “US companies will stop spending money on stock buybacks and spend it building sneaker factories instead,” but I guess that is roughly the theory. An aspect of modern finance that I confess is mysterious to me is: What do retail investors do? I mean, a lot of people who are not financial professionals seem to buy and sell stocks and options in their own accounts. I sometimes confidently throw around phrases like “read about stocks on Reddit” or “click a button on a phone app” or “seek revenge on short sellers” or “trade stocks because it is more fun than other entertainment alternatives” or “YOLO zero-day options on meme stocks,” but I have no great intuition for the process. I feel like I have a decent handle on how hedge fund analysts choose and purchase stocks, but the retail investors are a bit of a mystery to me. So I enjoyed this paper on “The Research Behavior of Individual Investors,” by Toomas Laarits and Jeffrey Wurgler. In 2007, a research firm “recruited a representative panel of [92,411] U.S. households that have agreed to install on their computers a data collection plug-in that records the URL address of each webpage visited. The data collected include the exact sequence of web pages visited and the amount of time spent on each page.” [5] Presumably the research firm sold this data to all sorts of marketers, but over the years it has also given it to academics who wanted to study various aspects of people’s online behavior. Laarits and Wurgler wanted to study people’s online stock research, so they got this data set and focused on the 484 households in the sample who did online stock trades. Arguably what individual investors did in 2007 tells you nothing about what they do in 2025 — Robinhood hadn’t even been invented yet! — but their findings still seem intuitively plausible today. [6] There are various high-level aggregate findings: The median individual investor spends six minutes per trade on research about the tickers traded. The mean individual investor spends 29 minutes. The median investor conducts most of this stock research in the 24 hours before a trade, and most of that time in a burst immediately before the trade. … Typical investors spend only a fraction of their research time at their broker’s domain. Disparate finance news sites, and especially Yahoo Finance, constitute a majority of stock-related research. .. Most trades are preceded by the presentation of a snapshot page which includes a set of brief price and fundamental statistics and a graph of intraday prices. Many investors do not pursue research beyond this page. When individual investors do go beyond the snapshot page, they spend by far the most time on price charts and price-related information. Analysts’ estimates are consulted less frequently, followed by assorted other fundamental and technical information. Risk statistics such as beta or volatility are of little apparent interest. If you had asked me “how much attention do individual investors pay to a stock’s beta” I would confidently have answered “exactly zero,” so that makes sense. But my favorite part is not the aggregate statistics but this little depiction of a day, or rather 14 minutes, in the life of one retail trader in 2007: A stylized extract of raw data illustrates the level of detail that it may include. Table 1 reports fourteen minutes of a browsing session [on March 23, 2007]. The session may begin at any link. This particular investor is a motorsports fan [who starts at formula1.com] but soon switches to CNBC.com, where she clicks a link providing current data on several U.S. and international stock market indices, the US 10-year Treasury yield, and the USD-Euro exchange rate. After a minute at that page, the investor logs into a brokerage account. Within her online broker’s research pages, she seeks out the day’s most active names, which on that day included ImClone (IMCL). Based on our own investigation, IMCL enjoyed good news for its cancer drug’s prospects. Our investor then consults the quarterly earnings performance for IMCL. From the link, we can infer that earnings were presented for the prior three years and estimates were shown for the next two years. In a separate panel, the chart showed the daily volume for IMCL over the prior three years, as well as a 13-day moving average. Further analysis of IMCL took place on the highly popular Yahoo Finance website. The investor obtains a quote on symbol (“?s=”) IMCL and then looks up the latest analysts’ estimates (“ae”). Following a check-in with race results, the investor returns to her brokerage’s page and takes a different tactic. This time, she looks for trading ideas through a stock screener, in particular stocks with expected EPS growth of at least fifty percent over the next fiscal year. This would have yielded many results, Google (GOOG) among them. A click or two later, the investor comes to a snapshot page, which presents many types of financial and price information on the given stock in an abbreviated form. After looking at a price chart, the investor enters a market order to buy (“ordertype=1”) Google shares. Then she logs into e-mail and proceeds with other activities. Honestly that seems somewhat more thorough than I would have guessed. Google closed at $11.56 that day; it ended the year at $17.30 and closed yesterday at $157.04 so, you know, fine trade, no objections. Anyway I assume this is different now — more Reddit? phones? asking ChatGPT what stocks to buy?— but it is still interesting anecdotal data. I suppose some research firm somewhere is still collecting this sort of click data for marketers; I wonder if any hedge funds use it. “A lot of people are looking at the GameStop snapshot page, let’s buy some.” Or “let’s sell some.” Elsewhere in academic research on the effect of financial innovation on households, here is a 2024 paper asking: “Have cashless payments reduced the incidence of upper aerodigestive foreign body insertion?” The answer is yes, so if you work in fintech you can go ahead and tell your parents that you are actually saving lives. It might be the case that the market for normal financial products is pretty saturated. “Pay us $X now, and if Event Y occurs, you will receive Payoff Z”: There’s probably a product like that for most events that people anticipate, and if there isn’t, there’s probably a good reason that no one can build it economically. But there probably are some events that people aren’t thinking of, and if you have an unusual cast of mind you could think of them and build some innovative financial products. We talked last year about “science fiction trusts and estates lawyers,” who are in the business of helping people do financial planning for their frozen heads when those heads are reanimated in 200 years and need money. If you are offering retirement planning, or college financial planning, you are competing with a lot of big asset managers. But if you are offering reanimated frozen head financial planning, you are … not. Like Larry Fink does not go around talking about BlackRock’s products for reanimated frozen heads. There is a lot of open space. Also: You might not need to be that good at it. Both in the sense that, like, your investment performance can be worse (and your fees higher) than BlackRock’s, and also in the sense that you don’t absolutely need to solve the problems you are addressing. In a mature competitive market, people buying 200-year reanimated frozen head trusts would want to buy them from providers who are likely to be around in 200 years and not lose the money, and regulators would make sure that those providers were appropriately capitalized and monitored. But in the actually existing 200-year reanimated frozen head trust market, ehhh, possibly not. I do not know how broadly applicable the lessons here are, but it’s not just frozen reanimated heads. The opportunity that I think about all the time is OpenAI’s threat to its investors that “it may be difficult to know what role money will play in a post-[artificial general intelligence] world.” OpenAI gestured at that idea to justify structuring moderately unusual equity investments, but if you took it seriously what would you do? If you are an institutional allocator, how do you hedge the risk that the role of money might change in a post-AGI world? More to the point, if you are a salesperson of financial products, what sorts of hedges are you pitching to allocators? “Own AI stocks,” fine. “Bitcoin,” probably, somehow. But I feel like you could find much weirder things and get some takers. Anyway here’s a New York Times story that is closer to the frozen heads thing, but with a religious rather than science fiction flavor: Swami Nithyananda … claimed miracle powers, like helping the blind see through a “third eye” or delaying the sunrise by 40 minutes. “I am a totality of unknown in your life. I’m the manifest of un-manifest,” he said in one sermon. “The moment you sit in front of me, enlightenment starts.” During a conversation in front of a large crowd, he endorsed the idea of “the world’s first inter-life reincarnation trust management.” Rich people like Bill Gates or Warren Buffett could invest a few billion dollars in a trust; Nithyananda said he possessed the knowledge system to ensure they got the money when they were reborn. That would be important, Nithyananda’s interlocutor said, “because it is possible Bill Gates will be born very poor, Warren Buffett may be born in some African village as a very poor guy.” Inter-life reincarnation trust management! Definitely not a product offered by BlackRock. It does not sound like they actually got a meeting with Warren Buffett to pitch this, but surely someone would bite. Anyway the story is about how he and his “self-proclaimed United States of Kailasa” have gotten in trouble for other alleged deceptions, but this one I like. How North Korea Cheated Its Way to Crypto Billions. Cayman Islands Builds $74 Billion |