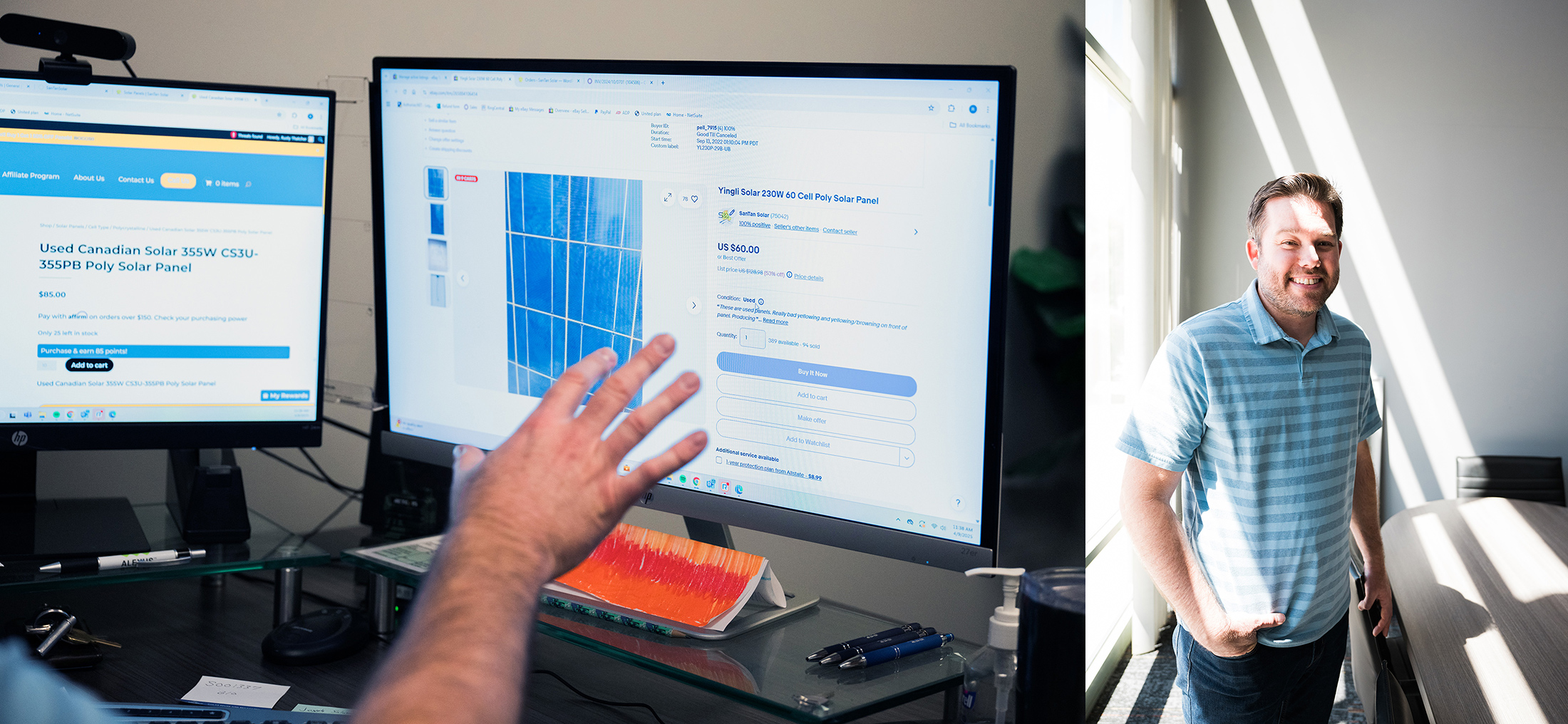

| By Shoko Oda Todd Dabney, who’s been going to the Burning Man festival since 2011, needed a way to keep his tent cool under the baking Nevada sun. So the IT consultant created what he calls “the ultimate swamp cooler” out of a heavy-duty plastic storage container, pumps, tubes and a fan. Powering the device is a 385-watt JinkoSolar panel that he snapped up on Craigslist several years ago from a nearby seller for $100. Dabney recalls that the seller was upgrading his solar array and getting rid of his current panels, which were about five years old. “There was no reason to buy new panels” for the cooler, he says. “I knew I was taking this to Burning Man, and it’s going to get dusty and beaten up.”  Todd Dabney’s DIY solar-powered evaporative cooler, left and middle, undergoes testing in 2019. Dabney, right, helps disassemble a geodesic dome at Burning Man in Black Rock City, Nevada, in 2023. From left: Courtesy: Todd Dabney; Courtesy: Stuart Sharpe As factories turn out more and more new panels, the supply of used ones increases in turn. Dabney is among a group of solar shoppers in the US who opt to buy them secondhand, often through listings on eBay, Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace. On message boards like Reddit’s r/solar and the DIY Solar Power Forum, thrifters can share their experiences and swap installation tips. Pre-owned panels are an attractive option for the frugal, as well as DIY enthusiasts, tinkerers and homesteaders. Their cost varies with age and output. Older panels, which usually have lower wattage, can be found online for under $50. Newer ones tend to have higher wattage and can cost several times as much. But any secondhand panel from the next town over will be tariff-free, whereas the majority of new panels installed in the US are imported, so subject to a levy. Read more: US Solar’s Hoarding Habit Will Help Blunt Sting From Trump Tariffs Giving the modules a second life has environmental benefits, experts say, and as more solar is installed globally, the niche used market could grow. Arizona-based SanTan Solar sells both new and used panels through its website and eBay. Its parent company, Fabtech Solar Solutions, runs a solar recycling business that takes panels from decommissioned projects and tests them for quality. SanTan sells the used modules with a one-year warranty.  Rusty Thatcher, a sales manager at SanTan Solar, shows panels for sale on the company’s website and on eBay. Thatcher describes the buyers of used panels as “energy independent” and “budget conscious.” Photographer: Caitlin O’Hara for Bloomberg Green Interest in pre-owned panels spiked during the Covid-19 pandemic, when Americans were spending more time at home, according to SanTan sales manager Rusty Thatcher. “The primary end-users are people that are more energy independent, that are really more budget conscious — they’re really looking for a cheap alternative to other energy sources,” Thatcher says. They might want to set up a solar system for their RV or need to replace part of an existing array, he adds. Going used also avoids sending working panels into the waste stream prematurely. The International Renewable Energy Agency estimates that the cumulative waste from photovoltaics will reach 4 million tons globally in 2030, and almost 50 million tons in 2040. Read more: The Quest to Make Clean Energy Even Cleaner Panels typically have a warranty of 30 years, but many don’t reach their full lifespan before being replaced. Their manufacturing results in the same environmental impacts whether they’re in use for three years or three decades. “Once you’ve manufactured a PV panel, extending its lifetime through reuse amortizes the sunk, or embodied, environmental impacts over more electricity generation, reducing the per kilowatt-hour impacts,” says Garvin Heath, principal environmental engineer at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and an expert on lifecycle assessment of energy technologies. What are the drawbacks of buying used? Continue reading here. This story is part of Bloomberg Green’s spring cleaner tech package exploring the money, politics and people shaping the energy transition. Check out our other coverage: |