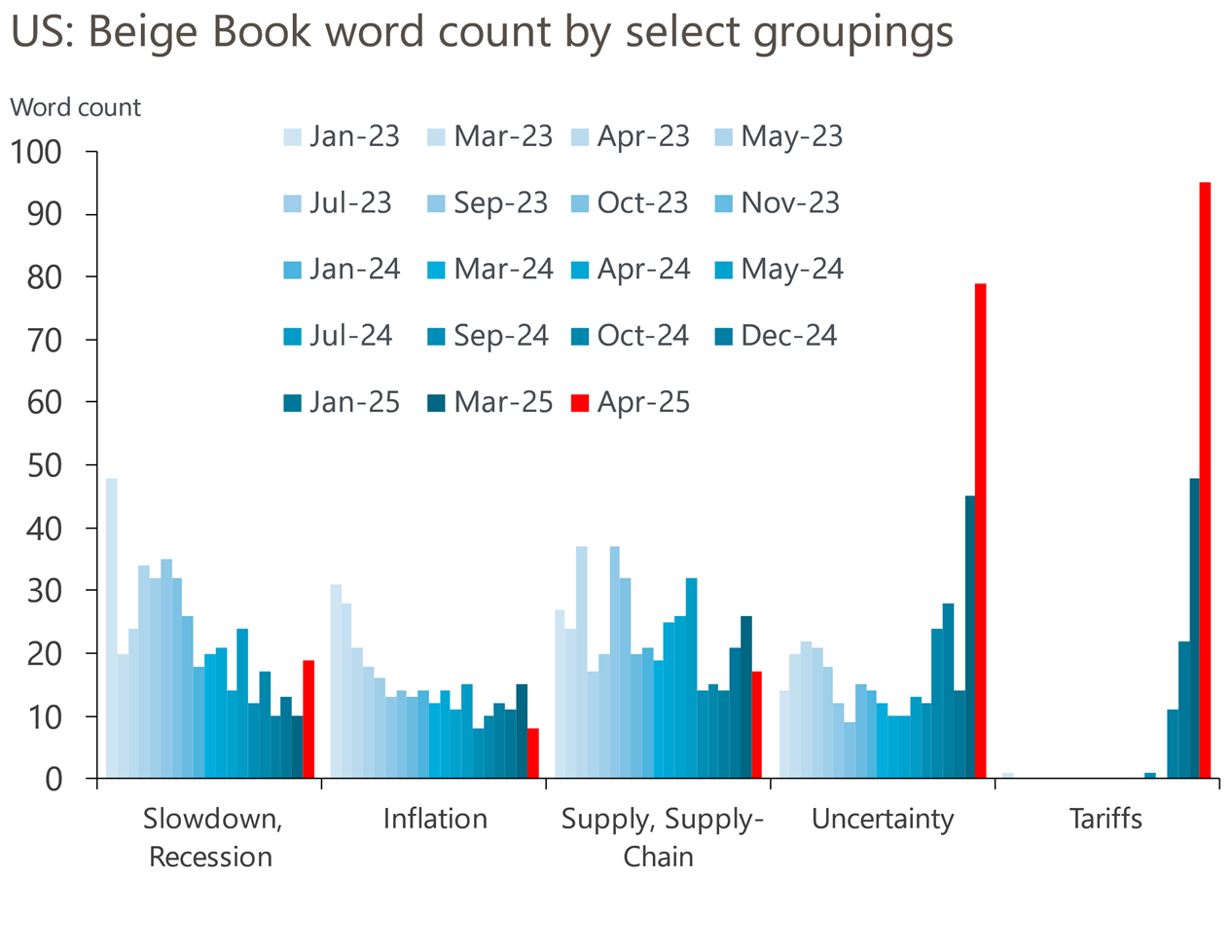

| Global markets have enjoyed something of a relief rally, as we now reach three weeks since Donald Trump launched his Liberation Day tariffs on an unsuspecting world. It seems to be about two things: The news that Trump has no intention of firing Fed Chair Jerome Powell, and that he intends to be “very nice” to China on trade. There is much to debate over exactly how much the president conceded, but the key point as far as Mr. Market is concerned is that he’s shown that there is indeed a “Trump Put” — an option that allows investors to limit their losses if shares fall. The strike price is lower than had been hoped, but the key is that Trump has shown that when challenged, he blinks. If that seems unfair, the circumstantial evidence from the performance of the S&P 500 since Liberation Day looks damning. The gentleman, it seems, is for turning: Actions matter more than words, so this is a big deal. However, the underlying behavior of markets suggests that this wasn’t much of a relief rally. Since Liberation Day, the only sector of the S&P 500 that has actually risen is consumer staples, the traditional destination for the nervous. The performance of staples relative to consumer discretionary companies, and of stocks relative to bonds, confirms ongoing savage negativity following the optimism of the post-election Trump Bump: And there’s one particular harbinger of concern. Walmart Inc. was the only stock in the S&P 500 that rose between the market peak in 2007 and the low in 2009. When it is beating the overall market, it’s a clear sign that investors don’t think much of the economy. And Walmart is doing well of late, hitting an all-time relative to the market: So the market is reassured that it seems to have the power to pull the president back from the brink of making a major mistake. That’s important, but it doesn’t mean everything is great. Particularly, the retreat from US stocks to other markets is ongoing. The turnaround this year to date is spectacular: Despite the relief at signs that they can bully the president, investors are still plainly unhappy, and the direction of travel for the market from here is not clear. That’s in large part because the U-turns could be more complete. Trump wants tariffs on China to be “substantially lower,” but not negative, while Scott Bessent then assured everyone that the cuts won’t be unilateral. In other words, the administration wants to make a deal to reduce tariffs from their current absurd level, which we knew already. The shift in rhetorical tone is important; far more precision is needed before we can lift the uncertainty. That’s problematic because uncertainty in itself inhibits economic activity and money-making. The Federal Reserve’s regular Beige Book, a collation of anecdotes and observations from the different branches’ contacts with business, illustrates the problem neatly. The latest, published Wednesday, is dominated by the uncertainty created by tariffs. Oxford Economics keeps this handy breakdown of the themes that dominate each edition. It speaks for itself:  Source: Oxford Economics While tariff uncertainty persists, the risk is that it will so inhibit businesses as to drive the economy into an unnecessary recession. Once that possibility can be ruled out, then a consistent market advance could happen. What Other Puts Are Available? | Investors would rather have better defenses. Trump looks as though he is movable, but you wouldn’t want to bet that any given level in the market will turn him around. And nothing else works. To quote Viktor Shvets of Macquarie: Capital markets are proving to be the only guardrail with sufficient power to defang the most extreme outcomes. Neither legislature, corporates nor judiciary seem able to restrain the surging executive power that recognizes few checks and balances.

He added that while the selloffs had forced the president to dial back the rhetoric, his most recent words run counter to his lofty long-term aims of remaking American society and the economy by changing the world. With decision-making evidently erratic, Shvets predicts “rolling chaos over years to come.” If you can’t rely on a Trump Put with a fixed strike price, then predicting a change in policy requires knowledge of, first, the Kremlinology of who has the president’s ear at any one time (should we listen to Bessent? Navarro? who?), and, second, the state of the president’s mind. Investors know virtually nothing about either. That shrouds future moves with uncertainty and effectively forces them to show more caution, or in more technical terms to demand greater risk premia and therefore lower prices. As Hubert de Barochez of Capital Economics puts it, with some diplomacy: The fact that the rally was sparked largely by conciliatory remarks from US President Trump – whose rhetoric is notoriously volatile – raises questions about its durability.

A firmer guardrail involves the electorate, not the market. Bankim Chadha of Deutsche Bank AG has reduced his target for the S&P 500 for the year, citing doubts over whether tariff policies will be abandoned before they have already driven the economy into a recession. The latest market-driven U-turns don’t guarantee a positive outcome, but there is hope the president’s approval numbers suggest a clearer turning point ahead: Chadha’s base case remains “a significant rally on a credible relent on trade policies, with a target of 6,150 by year-end” (a 14% gain from here). But that credible relent would, he thinks, require a much lower approval rating, perhaps in the low 40s or mid-30s. By then, it may be too late: “The risk to our view is we don’t get a relent before the nonlinearities of recession kick in.” Approval tends to move with consumer confidence which, as Chadha shows, was really bad for Joe Biden. Trump’s rating remains well above Biden’s when he left office, but falling confidence suggests it has further to drop. Markets see ending the current virtual embargo on China, and the removal of practically all tariffs announced this year on everyone else, as the ultimate put. The risk, still not vanquished, is that it doesn’t come until too late. |