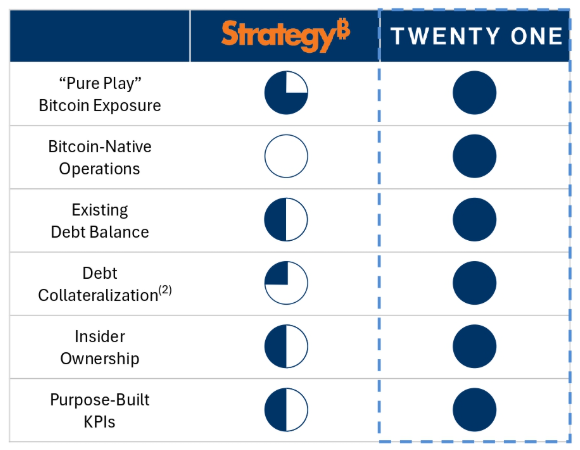

| The basic situation is that US public equity markets will pay about $2 for $1 worth of Bitcoin. I don’t know why this is, and I am not especially happy about it, but it’s true. If you have one Bitcoin, you can sell it on a crypto exchange for about $93,000, or you can sell it on a US stock exchange for about $186,000. Therefore, you should sell Bitcoins on the stock exchange, so people do. The most famous example is MicroStrategy Inc. (now just Strategy), which has built a perpetual motion machine out of buying $1 worth of Bitcoin, seeing its stock go up by $2, and selling more stock to buy more Bitcoin. Because this keeps working, people keep copying it, and I keep talking about them. Originally, this approach was taken by public companies (MicroStrategy and then some imitators): Those companies already had publicly traded stock, so they could pivot to buying Bitcoin (or other cryptocurrencies) and watch their stocks go up. But this strategy is not that natural a fit for most US public companies. Most companies are in the business of doing their business, so pivoting to selling stock to buy crypto would be kind of weird. This strategy is a natural fit for crypto investment funds, though, so they really ought to get into the business of acquiring US public companies and turning them into pools of Bitcoin. So we talked this week about Upexi Inc., a tiny public company that got acquired by a crypto investment firm and turned into a pot of Solana. Its stock roughly quadrupled, meaning that it is selling $1 worth of Solana for $4 on the stock exchange. Great work if you can get it. And you can get it! If you run a crypto investment fund it is absolute malpractice not to acquire a small, not-particularly-operating US public company; your fund’s value will at least double immediately. You know who has a big pot of crypto? Tether. Here’s this: An affiliate of Cantor Fitzgerald LP is teaming up with stablecoin issuer Tether Holdings SA and SoftBank Group to create a new company called Twenty One Capital Inc. with the goal of accumulating Bitcoin, the latest company to emulate the business model of Michael Saylor’s Strategy. Twenty One said it expects to launch with more than 42,000 Bitcoin, worth about $3.9 billion at current prices, making it the third-largest Bitcoin treasury in the world, according to a statement from the company on Wednesday. Tether will contribute $1.5 billion of Bitcoin to the new company, while Bitfinex, a Tether-affiliated exchange, and SoftBank plan to put in $600 million and $900 million of the cryptocurrency, respectively, according to a person familiar with the matter who asked not to be named since the discussions were private. The company said it has entered into an agreement for a business combination with Cantor Equity Partners Inc., a special-purpose acquisition company sponsored by an affiliate of Cantor Fitzgerald. Shares of Cantor Equity Partners surged 21% to $13 on Wednesday. Cantor Equity Partners is, for these purposes, a small, not-particularly-operating US public company. In fact it is a SPAC, so it is not an operating company at all; as of Tuesday it was a pot of cash with (1) approximately $102 million in the pot and (2) a market capitalization of approximately $104 million. [1] Each share of Cantor Equity Partners represented a claim on about $10.35 of the company’s cash [2] — plus some upside if the SPAC found a deal — and traded at about $10.60. Fine. On Wednesday, Cantor Equity Partners announced a merger between (1) its pot of cash, (2) Tether’s pot of Bitcoins, (3) Bitfinex’s pot of Bitcoins and (4) SoftBank’s pot of Bitcoins. Tether, Bitfinex and Softbank will contribute a total of about 36,210 Bitcoin, worth about $3.4 billion, and take back stakes in the combined company; for its $100 million pot of cash, Cantor Equity Partners public shareholders will get about 2.9% of the company. [3] (The $100 million pot of cash, plus some other contributions, will be used to get the company to 42,000 Bitcoins.) That roughly makes sense: $3.4 billion of Bitcoin plus $100 million of cash equals $3.5 billion of value in the pot, and $100 million is about 2.9% of $3.5 billion. The merger math here is pretty straightforward; everybody (Tether, SoftBank, the public shareholders) is getting a stake in the company roughly proportional to what they put in. At noon today, Cantor Equity Partners was trading at about $28.34 per share, almost triple its pre-deal price. That implies a value for Twenty One’s 36,210 Bitcoins of about $9.8 billion, [4] or about $270,000 per Bitcoin. Again, Bitcoin is trading at around $93,000 today on crypto exchanges. If you can sell Bitcoin for $270,000 on the Nasdaq, you’d be crazy to sell it for $93,000 on a crypto exchange. As is traditional in these sorts of situations, the focus is on the vision for the future of finance rather than the simple math. Here’s the press release: “Markets need reliable money to measure value and allocate capital efficiently,” said Jack Mallers, Co-Founder and CEO of Twenty One. “We believe that Bitcoin is the answer, and Twenty One is how we bring that answer to public markets. Our mission is simple: to become the most successful company in Bitcoin, the most valuable financial opportunity of our time. We’re not here to beat the market, we’re here to build a new one. A public stock, built by Bitcoiners, for Bitcoiners.” ... Twenty One is structured to be a day one Bitcoin-native company that will strategically allocate capital to increase Bitcoin per share. Twenty One intends to develop a corporate architecture capable of supporting financial products built with and on Bitcoin. This includes native lending models, capital market instruments, and future innovations that will replace legacy financial tools with Bitcoin-aligned alternatives. As a pro-Bitcoin advocate, Twenty One plans to produce original Bitcoin-focused content and media. This pure-play approach will offer investors access to a public company that combines Bitcoin exposure with an operating business building Bitcoin-native products and services. Here are investor presentations for convertible note and equity investors; the deal was apparently codenamed “Project Mystery.” The presentations include this chart comparing Twenty One to MicroStrategy:  Source: SEC.gov. The top point here is that MicroStrategy is not quite “pure play” Bitcoin exposure: It also has a software company attached to its pot of Bitcoins. Twenty One, though, really is a pure pot of Bitcoins, albeit one with plans for “future innovations that will replace legacy financial tools with Bitcoin-aligned alternatives,” so — I suppose — it ought to trade at a premium to Strategy. One dollar of Bitcoin in Strategy’s pot is worth only $2 on the stock market; $1 of Bitcoin in Twenty One’s pot is, apparently, worth $3 on the stock market. A lot of people in traditional finance, certainly including me, like to make fun of crypto. There is a lot to make fun of. But who is traditional finance to talk? The uncomfortable fact is that the stock market will pay much more for crypto than the crypto market will: Packaging Bitcoin into a stock makes it much more valuable. The crypto enthusiasts on the stock market are more enthusiastic about crypto than the crypto enthusiasts in crypto. It looks a little bit like crypto keeps playing a prank on the stock market, and the stock market keeps falling for it.  | | | One way to think about crypto is that it is a way to enable “permissionless innovation.” A lot of the way traditional finance works is that you have a good idea but you have to have connections and get buy-in from regulators and investors and counterparties to make it happen. “This product should exist” is a starting point for discussions; you can’t just go make it. Whereas in crypto everything is built out of composable open-source public code; if you want to build something to interact with crypto markets, you just build it. You don’t need to have discussions with incumbents and regulators; you don’t need connections and pedigree. Crypto can move faster, and smart creative people can have a big impact without spending years paying dues and building connections. Similarly! Similarly. Similarly. In the past, if you wanted to hand a big bag of cash to the US president, it would be hard. You couldn’t just walk up to him and give him the bag. You would need to know the proper channels to go through; you would need some way in. Politically connected people, people familiar with US campaign finance laws, people who hired high-powered lobbyists, could perhaps get an opportunity to hand a bag of cash to the president. But if you just won the lottery and decided “I would like to put a million dollars in a bag and hand it to the president so he will talk to me for 10 minutes,” it would not be immediately obvious how you might go about doing that. Also, in the past, if you had tried to hand a big bag of cash to the US president, he might have said “no thank you,” though this is not essential to the analysis. Crypto really truly does solve this problem, if it is a problem, if it is a solution: President Donald Trump will have dinner with the top 220 holders of the Trump memecoin, the issuers of the cryptocurrency announced on Wednesday. At the “intimate private dinner” on May 22 at Trump National Golf Club near Washington, Trump will talk about the future of crypto, according to the organizers. People who want to participate have to register, and a leader board of the top Trump coin holders will be kept to determine attendees. The top 25 Trump coin holders will also be invited to a reception before the dinner with the president, and will be given a tour of the White House. “From April 23 to May 12, your average $TRUMP balance determines your spot,” according to the Website advertising the dinner. “Get $Trump Memes and climb the ranks.” It is the democratization of … bribery? Now everyone can compete on a level playing field to hand the president money, and whoever hands him the most money gets dinner with him. I mean! Okay! Incidentally. Schematically, the way meme coins are mostly supposed to work is: - There’s some meme, someone gets attention, etc.

- To capitalize on this attention, a meme coin is created, perhaps by the person who got all the attention.

- Some of the coins are sold to the public, while some are reserved for the creator who is perhaps the subject of the meme.

- But, at least as a matter of best practices, the creator isn’t supposed to sell all those tokens immediately. That is called a “rug pull” and is viewed as unsporting. This makes absolutely no sense to me — if you have 15 minutes of fame, why should anyone expect you to wait 16 minutes before cashing out? [5] — but it seems to be the (frequently violated) norm. If you create a meme coin, you are supposed to be in it for the long haul; you are supposed to be pursuing long-term meme value, not just a quick buck.

- So the meme coin has some sort of lockup schedule, where the creators and insiders have to wait a while before selling most of their tokens, to incentivize the creation of long-term value.

- How do you create long-term value in a memecoin?

- Well, every time another slug of coins gets unlocked, you have to do something attention-grabbing to revive the meme and make your coins more valuable when you sell them.

And so: Last week, crypto traders braced for the start of what are known as unlocks, or releases of a large swathes of the memecoin to its investors and insiders. Some 200 million Trump memecoins became available at launch on Jan. 17, and another 40 million were unlocked last week. CIC Digital LLC, an affiliate of the Trump Organization, and Fight Fight Fight LLC collectively own 80% of the coins that are subject to the unlock schedule, according to the coin’s website.

There will be selling pressure, from the unlocks, and buying pressure, from the fact that “from April 23 to May 12, your average $TRUMP balance determines your spot.” This is how you do it! I don’t know what it is, exactly, but this is certainly how you do it. You can read various news articles quoting ethics experts howling into the void about this, but why would you do that. One model is that a private equity firm has expertise in the general problem of “running companies.” Private equity managers might not be domain experts in widget manufacturing or accounting software or pest control, but they should be good at solving the problems that are common across lots of different kinds of companies. Therefore, they can buy lots of different companies and make them more valuable, by applying the general company-running skills that they possess and that others don’t. Historically private equity’s “general company-running skills” consisted largely of noticing that lots of companies (1) could handle more debt and (2) might benefit from giving executives more equity ownership, but that low-hanging fruit has largely been plucked, and now private equity firms invest more in operational expertise. This is not the only model of private equity, and in some circles private equity gets kind of a bad rap. Instead of “private equity has a generalized skill of running companies,” you might have a model like “private equity acquires companies, over-levers them, strips them for parts and leaves other stakeholders with the fallout.” Private equity is, on that model, a rapacious business; its returns come not from being good at running companies but from being particularly cold-blooded about maximizing its own take. Of course even if the first model is correct, that might lead private equity to cold-bloodedness. Perhaps cold-bloodedness is the best way to run a company. Perhaps, with its generalized expertise, a private equity firm will discover that being mean to employees generally increases the long-term value of companies, so it does that. But perhaps not. Perhaps being nice to employees generally increases the long-term value of companies, and a private equity firm, with its expertise, will discover that and thus become particularly nice. Private equity will buy insufficiently nice public companies, make them nicer, increase income and flip the new nicer companies for a profit. It will spot a market inefficiency — managers who aren’t nice enough — and correct it .Bloomberg’s Heather Landy reports on KKR & Co.’s investment in empathy: Pete Stavros, KKR’s co-head of global private equity and the driving force behind its employee ownership campaign, … did notice over the years that there were certain types of leaders at KKR companies who produced better results in the columns tracking culture data. Often they were women, immigrants, or people who grew up poor or held deep religious beliefs. He suspected there was something in their background that helped them connect with their employees. Was empathy, he wondered, their common trait? Stavros wasn’t sure how to prove that or what it portended for leaders who didn’t fit those profiles. But after a chance encounter with a Stanford University psychologist, he got some answers. The findings are already changing how KKR trains senior leaders inside the firm and across its portfolio. … KKR is now piloting three different training programs designed to increase empathy. Leaders are working with Zaki on building skills such as active listening. They’re also being sent on excursions facilitated by the Financial Health Network to explore how people in their communities get by. And they’re being put into Japanese-style kaizen meetings, in which people up and down the hierarchy find ways to improve the business. “Our job is to find good companies that we can make a lot better,” Stavros says. “Because how could we say we’re optimizing a business if 40% of the workers are quitting every year?” If making companies a lot better requires making their bosses a lot nicer, then, in its ruthless pursuit of profits, KKR will just have to do that. I wrote yesterday about two ways that big institutional investors can invest in private equity: - They can invest in a private equity fund, which will use their money to make deals, and will charge them a 2% management fee and 20% of the profits; or

- They can co-invest alongside the private equity fund, which gives them the option to say no to deals, and which can involve lower fees.

I suggested that co-investment is broadly nice for the institution (more flexibility, lower fees), but bad for the private equity fund manager (less committed capital, lower fees), and so the mix between fund investments and co-investments will depend on the relative power of the two sides. But a couple of readers emailed to point out an important nuance, which is that “a basket of options is worth more than an option on a basket.” When a private equity manager raises a fund, it charges its investors a performance fee of (say) 20% of the return of the fund. The return of the fund is the profits on its winning deals minus the losses on its losing deals. If it does 10 equal-sized deals in a $1 billion fund, and seven return +30% while three return -20%, the fund’s overall return is +15% and the sponsor will earn a $30 million performance fee. But if it does a co-investment, it will generally charge its co-investors a performance fee on that deal: The investor is making a single investment decision in that deal, not allocating to a fund. If the sponsor does 10 equal-sized $100 million co-investments, and seven return +30% while three return -20%, the sponsor will earn $42 million on the good ones (seven times times $30 million times 20%) and zero on the bad ones (there are no negative performance fees). As one reader put it: Even if you are paying a reduced fee on option #2 (coinvest with the fund), your returns (to the [limited partners]/pensions) might end up even worse since the [general partner’s] carry is no longer cross-collateralized. So if it's an area with wide variance (growth equity or venture), where you can have multiple companies go to zero with a few massive winners, your fee burden could end up higher.

If you are a limited partner and you are good at picking deals, this is still good for you: You’d rather invest in only the private equity sponsor’s winners, pay full fees on the winners, and avoid the losers entirely. But if you have no particular ability to pick the winners, at least investing in the fund means that your losses on the losers reduce your fees on the winners. We have talked a couple of times recently about the curious fact that (1) quantitative investing, (2) building large language models and (3) managing professional soccer teams are all approximately the same job. Also that job is approximately “astrophysics.” It is approximately the case that there is a general data-science-y skill set that is coming to dominate all of these apparently disparate fields, and that skill set is largely taught in certain hard-science graduate programs. And so you can move from a quant hedge fund to a soccer team and everyone is like “oh right of course that guy’s moving from a hedge fund to a soccer team, he has an astrophysics PhD, that all makes sense.” Twenty years ago soccer and investing and astrophysics were all very different jobs, but modern data science has discovered latent structures that make them the same job. Is hockey the same job? Oh I mean of course, how could it not be. Here is a fun Athletic article about Eric Tulsky, a PhD nanotechnologist who is “the general manager of the [National Hockey League’s Carolina] Hurricanes, the first person with anything close to his academic and scientific credentials to ever cross over to hockey in that role,” but not the last. Here is how he describes hockey: “A lot of what you’re doing in hockey is taking pieces of information that tell you a small piece of a story,” Tulsky said. “And sometimes those pieces of information conflict. Sometimes they’re missing things you need to know, and you piece it together and try and figure out what the underlying truth is, and that is an interesting puzzle to try to solve.”

“A lot of what you are doing in hockey is ice skating, hitting a puck with a stick and crashing into other people,” is how you might naively describe hockey, but the actual GM of the Hurricanes knows that hockey is in fact a data science puzzle. Also here’s how he hired a guy for his team (to do data science, I mean, not to skate): The NHL had released tens of millions of points of new data with the introduction of player and puck tracking, but it was such an enormously complex dump of information that it would take a special skill set to turn it into something he could use. … Because of what he saw in the tracking data, Tulsky believed his next addition needed to be someone who was working on autonomous vehicles — perhaps “a robot submarine,” he says now — and had an advanced mechanical engineering background. “I knew that that was the kind of problem that put people thinking about the kinds of data that we had and the kinds of problems we faced,” Tulsky explained. It goes without saying that there aren’t many robot submarine engineers working in NHL front offices. So Tulsky began a deep search through universities’ mechanical engineering departments. ... And that was how an NHL team came to fund the PhD research of a young engineering student named Jonathan Arsenault at McGill University in Montreal. His thesis, the first to be backed by a professional hockey team? “Quantitative Analysis of Hockey Using Spatiotemporal Tracking Data.” I like that the guy was in his prestigious mechanical engineering PhD program and his supervisor was like “so what will your dissertation be about? Is it robot submarines?” and he was like “no actually I was thinking of working on evaluating hockey players” and the supervisor was like “oh of course, yes, deep down that is also a mechanical engineering problem.” Corporate America puts Wall Street on alert over damage from trade war. Huge Stock Swings Are the New Normal for Frazzled Investors. Despite Trump’s Apparent U-Turn, Drawn-Out Capital Flight Could Still Hit U.S. Markets. Franklin CEO Says Some Institutional Investors Are Ditching US Stocks. Carlyle’s CEO Is Reviving Its DC Brand Just in Time for Trump Era. Elliott’s ‘lone wolf’: the hedge fund maverick waging war on Big Oil. Trump ‘eroding’ US brand, has made the country 20% poorer, Citadel chief says. Morgan Stanley to Sell Final $1.23 Billion X Debt Tied to Buyout. Ukraine fails to reach deal with investors to restructure $2.6bn of debt. Celsius Investors Urge Severe Punishment for Founder Mashinsky. Team Valuations Are Pushing Pro Sports Into the Arms of Private Equity. The |