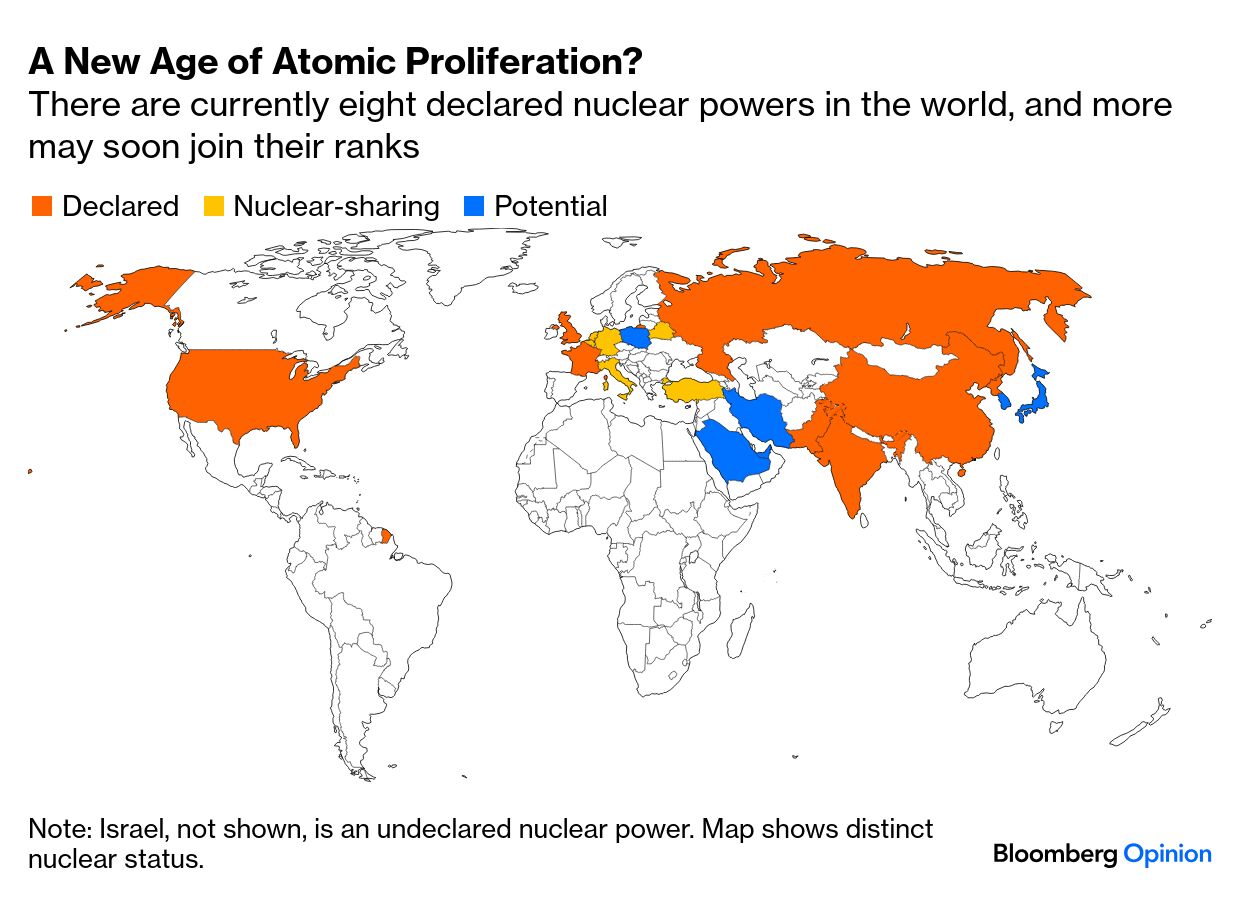

| This is Bloomberg Opinion Today, the special envoy for all sorts of overseas crises for Bloomberg Opinion’s opinions. On Sundays, we look at the major themes of the week past and how they will define the week ahead. Sign up for the daily newsletter here. This morning’s quick quiz is a two-parter: A) What US president insisted that “We owe it to our children to pursue a world without nuclear weapons”? B) Which said, “We seek the total elimination one day of nuclear weapons from the face of the Earth”? The first was Barack Obama, natch. The second was Ronald Reagan, demonstrating that the triumph of hope over experience is a bipartisan affliction. Obama had lots more to say on the subject: “We’ve succeeded in uniting the international community against the spread of nuclear weapons, notably in Iran,” he wrote in 2016. “The additional sanctions recently imposed on Pyongyang by the United Nations Security Council show that violations have consequences.” Over the next year and a half, North Korea launched ballistic missiles within 200 miles of Japan and conducted two nuclear tests — claiming, somewhat convincingly, that the second was a “missile ready” hydrogen bomb. Consequences, indeed. As for Iran, well, we have spent weeks watching President Donald Trump and his aides hem and haw and undercut themselves in talks with a regime in Tehran that clearly has no interest in a deal. You may be tempted to play a little “gotcha” here and remind me it was Trump who ripped up Obama’s nuclear agreement with Tehran. And I’ll gotcha right back that Iran started cheating before the signatures on the JCPOA were even dry, and the pact’s provisions would have expired between 2023 and this fall anyway. But, per Obama, what about the children??? As Hal Brands puts it, they are “entering a new nuclear era, one more complex, and potentially far less stable, than the nuclear eras that came before.” Here’s some complex instability: As Iran strings Trump along, Israel thinks it’s time to go in with guns blazing. “Trump is telling the Israelis to cool their jets (literally) while he tries to forge a peaceful arrangement. But he is equally clear that if talks collapse, the next step may well be joint US-Israeli strikes,” writes James Stavridis. “You can bet that serious planning for strikes is in progress at the Pentagon, US Central Command in Tampa, Florida, and Israeli Defense Forces HQ.” The negotiations can’t be helped by the Trumpian chaos surrounding America’s foreign-policy brain trust. It starts with Marco Rubio who, as I put it so cleverly a few weeks ago, has four jobs and zero backbone. [1] “Rubio, despite all his titles, is visibly not America’s top diplomat. That would be Steve Witkoff, a real-estate tycoon whom Trump has made special envoy for all sorts of overseas crises,” writes Andreas Kluth. “It is Witkoff, not Rubio, who has led negotiations with Russia over Ukraine, with Iran over its nuclear program and with Israel and Hamas over Gaza. As John Bolton, one of the four National Security Advisors in Trump’s first term, points out, not only does Witkoff have ‘no evident experience’ in any of these matters, but ‘his connection to Secretary of State Marco Rubio is unclear.’” Things aren’t particularly stable, either, in the only country to ever suffer a nuclear attack: Japan, where Hal just spent a week. “Japan faces growing threats in its neighborhood, from a bellicose China and a potentially provocative North Korea. But the state of America was the foremost worry of nearly everyone I met,” he writes. “For decades, the alliance with America has been the bedrock of Japanese foreign policy. If that alliance ever falters, drastic measures — like building nuclear weapons — might be the requirement of Japan’s survival.”  Drastic measures may also be a requirement for the political survival of South Korea’s new president, Lee Jae-myung. “The moment calls for a rethink in the US ally’s defense posture,” writes Karishma Vaswani. “Public opinion will likely compel Lee to seriously consider the case for nuclear armament, as a way to develop autonomous self-defense and reduce dependence on the US. With North Korea’s nuclear weapons program now widely seen as irreversible, sentiment has shifted dramatically. Polls consistently show that over 70% of citizens support developing their own nuclear deterrent.” “In Europe the same uncertainties about American intentions loom large. In every capital, the question hangs in the air: will Trump withdraw America from NATO, and US forces from Europe?” asks Max Hastings. “So desperate are governments to keep American forces on the continent that they are willing to endure barrages of insults, and indeed of tariffs, without risking an absolute breach with Washington. But it is hard to sustain alliances amid doubts about which side America is on, save its own.” Although he is writing about Europe, Max sums it up in words equally applicable to America’s allies in the Pacific, Middle East and elsewhere: “The US no longer represents a rock such as anchored the West for so many decades, but more like sand, shifting underfoot.” That’s not the sort of sandbox we want our children playing in. More Radioactive Reading: - Golden Dome Is a Chance for Superpowers to Make Space Safer — The Editors

- What D-Day Tells Us About How Tech Goes from Niche to Mass — Gautam Mukunda

- Why Are Today’s Strongmen So Obsessed With Muscle? — Adrian Wooldridge

What’s the World Got in Store ? - Apple developers conf., June 9: Apple Can’t Leave China, With or Without Tariffs — Catherine Thorbecke

- US CPI, June 11: Skimping on Inflation Data Is Not Worth the Risk — Jonathan Levin

- Poland CPI, June 13: MAGA-Backed Win in Poland Sends Europe a Warning — Lionel Laurent

Part of the impasse with the ongoing nuclear negotiations is that, on the one hand, the Iranians insist they need to enrich uranium for a peaceful nuclear power program and, on the other, the rest of us laugh uproariously. Well, nervously anyway. But for other countries, nuclear power is becoming less of a joke. Liam Denning tells us that America’s superpower rival is taking things seriously: “China hosts roughly half the nuclear power capacity under construction around the world.” It also creates a second nuclear dilemma for South Korea’s new leader. “Lee has promised to phase out coal, limit use of natural gas, and accelerate the building of wind and solar. His position on nuclear power, a major success story that was strongly supported by his impeached predecessor Yoon Suk Yeol, remains ambiguous,” writes David Fickling. “Three under-construction nuclear generators near Ulsan and on the east coast must be expedited.” Finally, while the Editorial Board believes the transition to renewables is necessary, it’s also risky: Consider the blackout in April that left 50 million people without power in Spain and Portugal, where 70% of energy of was being generated by wind and solar. “Are our grids adapting fast enough to a world of rising demand, new threats and cleaner power?” the Editors ask. “Traditional fossil fuel and nuclear power plants offer a built-in stabilizer: spinning turbines that store kinetic energy and act as shock absorbers, balancing sudden changes in supply and demand … Spain is planning to phase out its nuclear plants; in fact, more will be needed globally to provide ‘dispatchable’ backup — the on-call power that can be ramped up quickly when variable sources drop off.” Indeed, for much of the world, ramping up nuclear power makes sense. For Iran, sitting on the world’s third-largest oil reserves and the second-largest natural gas reserves, the urgency seems more laughable. Notes: Please send bastani sonnati and feedback to Tobin Harshaw at tharshaw@bloomberg.net. |