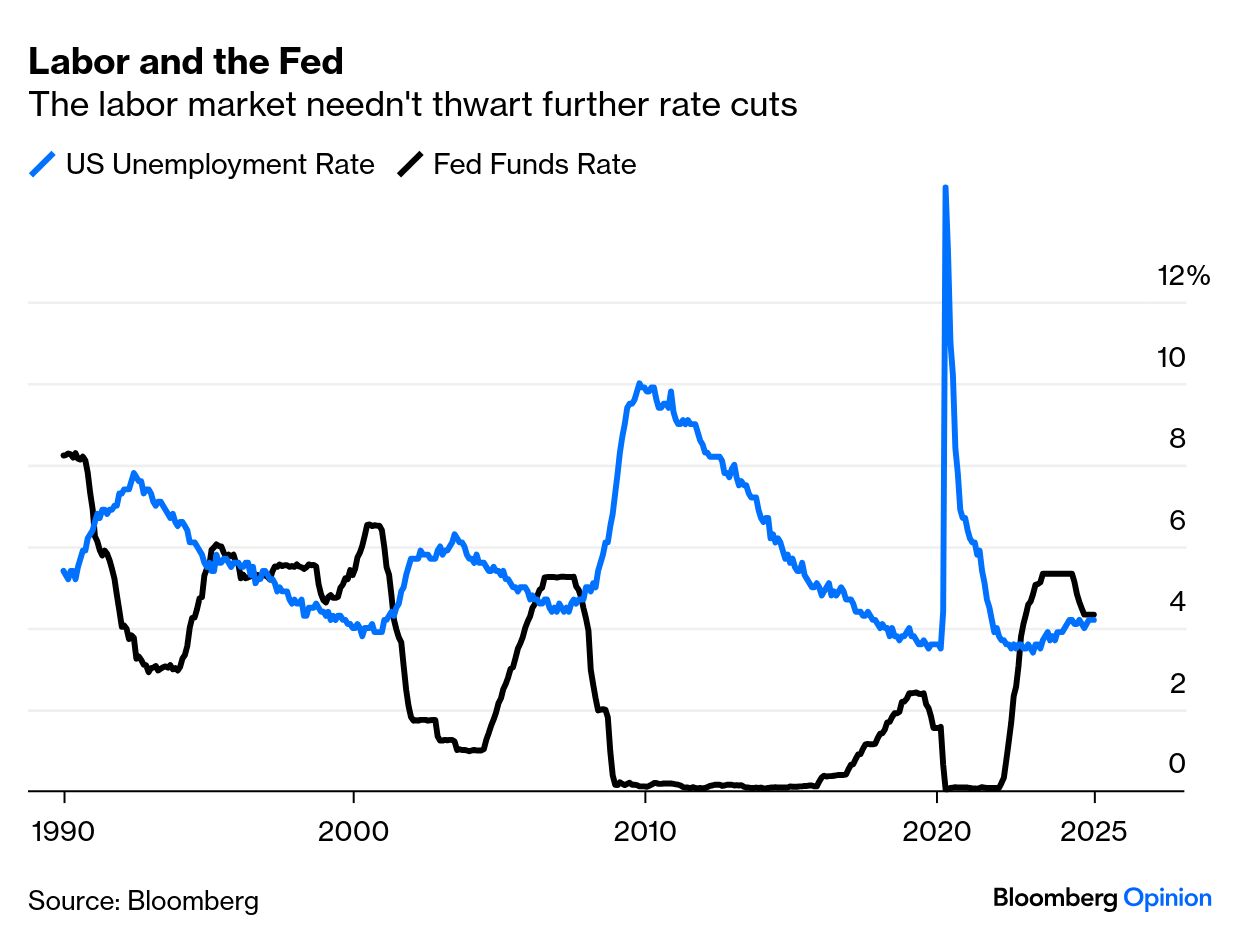

| There’s still no need for American investors to run for the hills. Payrolls increased again last month, with the unemployment rate unchanged. Everything is set calm. Last fall, unemployment was rising fast enough to trigger the so-called Sahm Rule, named for Bloomberg Opinion colleague Claudia Sahm, which predicts recessions from the propensity of unemployment to inch higher and then increase very sharply. It no longer seems as though we are poised for a sharp rise in joblessness: That makes life awkward for the Federal Reserve. Data last week offered signs of a slowing US economy, but this may reflect the way attempts to front-run potential tariffs are distorting people’s decisions. Using a simple measure, the effective fed funds rate is slightly above the unemployment rate, when for 15 years after the Global Financial Crisis it had been much lower. If unemployment ticks higher, history suggests interest rates will tumble. But that hasn’t happened yet:  Markets reduced still further the chances of more rate cuts this year. Overnight index swaps fully price only one 25-basis-point cut in 2025, with a 77% chance of a second. Meanwhile, last week brought a widely predicted rate easing by the European Central Bank, coupled with somewhat hawkish communications initially interpreted to make more cuts less likely. By the end of Friday, that move had reversed, leaving the gaps between US and European short-term rates, and between implied rates for December, almost exactly where they were on Jan. 1. After five months of intense uncertainty, central banks are back where they started: Rate differentials are of course critical to exchange rates. What implications does this have for the drama of the dollar and the purported end of US exceptionalism? Conventional wisdom can be a dangerous thing, but at present its judgment is clear. Seemingly everyone expects the dollar to fall. This is from Neelkant Mishra of Axis Bank in Mumbai: It is now consensus that the US dollar is likely to depreciate meaningfully over the next few years: The real effective exchange rate is at levels last seen at peaks in 1971 and 1985, the US government wants it, net international liabilities are at -90% of GDP, and primary income has turned negative.

The Federal Reserve’s own estimate of the real effective exchange rate (taking into account different rates of inflation in different countries) suggests the dollar is unusually strong, after the longest upswing since it was allowed to float with the end of the Bretton Woods agreement in 1971: This is not a quirk of adjusting for inflation. Using the DXY index (comparing to big developed markets), and the Bloomberg dollar index (including emerging markets as well), the pattern is clear that the dollar is still holding on to gains since the pandemic, and remains far stronger than it was at the onset of the Global Financial Crisis: But something important has changed. As we saw earlier, rate differentials between the US and Europe have barely changed since the beginning of the year, and yet the dollar is much weaker. This is very unusual, as illustrated by Robin Brooks of the Brookings Institution: Brooks offers two explanations for the divergence. The benign one is that equity flows are driving it. “Markets had bought into US ‘exceptionalism’ and are now reversing themselves on that theme.” Brooks call this a “cyclical reassessment of the US growth picture, expressed via equities.” Thus rate differentials matter less than usual. His less benign interpretation is “negative animal spirits, which rate differentials fail to capture” about reserve currency status. Brooks is “almost sure” that the former is the better explanation and remains bullish on the dollar for the longer term. In other words, this is about the currency being overvalued and due a fall, not any questions about its role in the financial system. These explanations are different, and refer to two different things: the dollar’s status, and its price. Brooks points out that the currency perked up in response to Friday’s employment numbers, which is exactly what’s supposed to happen. That suggests the dollar “is healthy and its behavior in line with the past decade, when it strengthened.”  Rules matter for the dollar to remain the essential currency. Photographer: Ting Shen/Bloomberg But much depends on timescale. The dollar’s status is secure for now because it lacks viable challengers. That may not last forever. Borrowing a list from Macquarie’s Viktor Shvets, a global currency and its issuer: - Must be convertible with no capital controls. (The euro and the yen also satisfy this, but not the yuan).

- Should run a current account deficit, to place sufficient funds in foreign hands. That rules out everyone bar the dollar.

- Needs a deep, liquid pool of assets; at this time only the US qualifies.

- Needs easy-to-use and secure settlement systems; SWIFT and CHIPS are the bedrock of dollar hegemony, “with no one else coming even close.”

- Must have sturdy, reliable domestic institutional pillars, with consistent rules-based policies. This is where the US is falling down; for all its flaws, the EU is more of a rules-based order.

- Should uphold global norms and rules — another area where the US is weakening.

- Have stronger-than-average economic growth — an advantage for the US over the EU and Japan.

For now, there is no alternative to the dollar, and there won’t be for many years. That said, the salutary effect of the Trump shock on Europe might just change that. If he proves to have administered just the kick to get the euro zone to forge a viable fiscal union, the euro’s chances of challenging the dollar rise significantly. And while the dollar will retain reserve status for a long time, Brooks’s dichotomy may not be helpful. Anatole Kaletsky of Gavekal Research argues that the long-term factors that could eventually end the dollar’s reserve status will take years, and in many cases might be reversed by future administrations. For the very near-term, the noise of each succeeding presidential social media post is driving everything. But the medium term, he contends, is predictable. Even though the US is nowhere near losing its leadership yet, “sentiment among investors about the sustainability of ‘US exceptionalism’ will be strongly influenced by how well (or badly) the US economy performs in the next year or two.” In other words, in this febrile environment, a cyclical downturn will be treated as evidence of a secular one. Kaletsky is expecting a US recession as the deleterious effects of the tariff confusion finally make themselves felt later this year, while prospects for China and particularly Europe are improving. Contrary to the usual cliché that when the US sneezes, the rest of the world gets pneumonia, he says: “This time, the US will suffer a bad case of flu, if not pneumonia, while the rest of the world will just blow its nose.” |