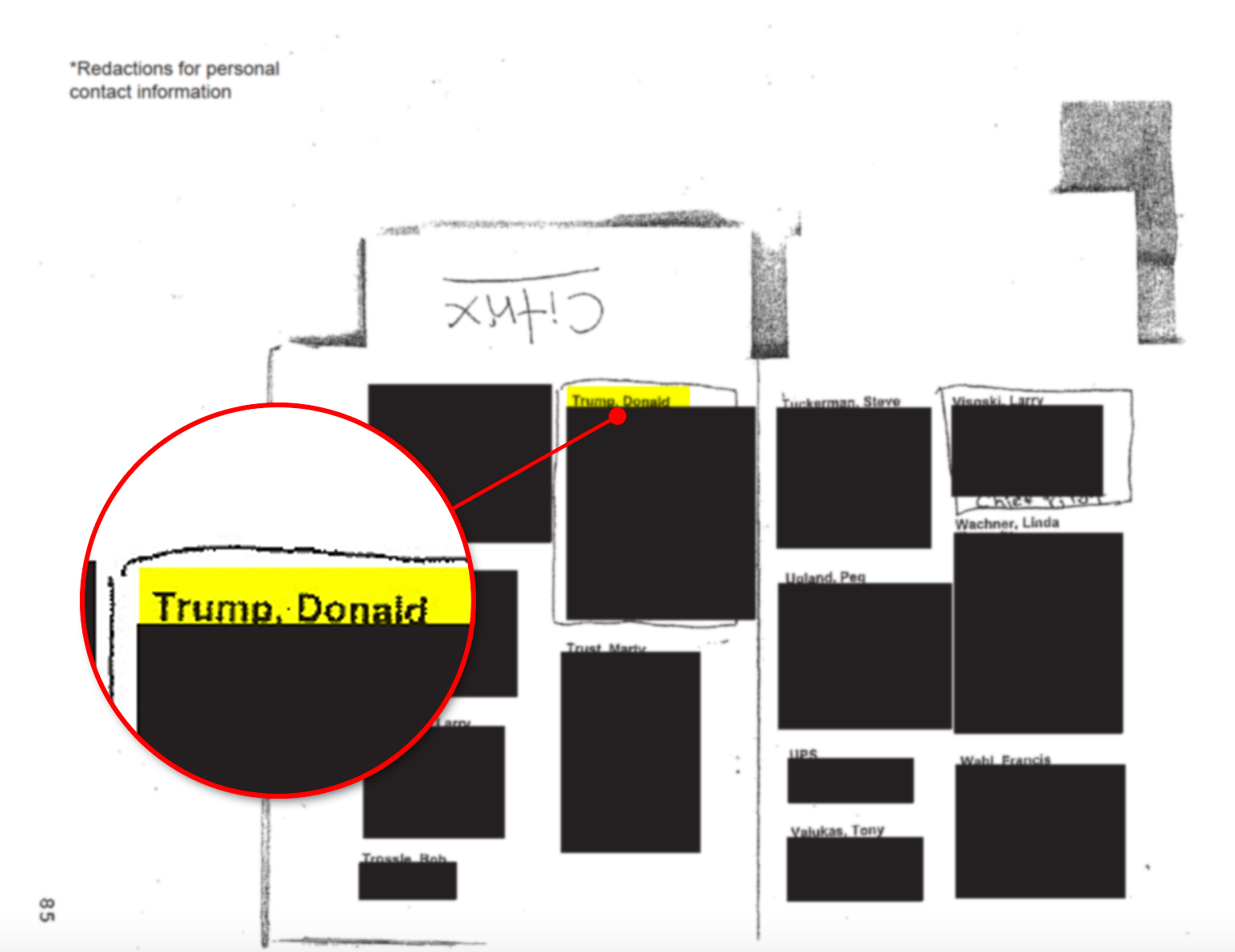

| Welcome back to FOIA Files! This week, I’m delving into the Jeffrey Epstein saga: We know from news reports that Trump’s name was in the Epstein files. But what hasn’t been reported is that an FBI FOIA team redacted Trump’s name—and the names of other prominent public figures—from the documents, according to three people familiar with the matter who were not authorized to speak with the media. That team, tasked with conducting a final review of the voluminous cache, had applied the redactions before the DOJ and the FBI concluded last month that “no further disclosure” of the files “would be appropriate or warranted.” From the government’s perspective, Trump was a private citizen when the Epstein investigation took place and therefore is entitled to privacy protections. Read on and I’ll explain. If you’re not already getting FOIA Files in your inbox, sign up here. ‘The most transparent administration in history’ | Before explaining the government’s rationale for blacking out Trump’s name, let’s recap. Along with aliens and JFK’s assassination, conspiracy theories surrounding the life and death of convicted sex-offender Jeffrey Epstein have long consumed MAGA. Epstein avoided federal sex-trafficking charges in 2008 when he agreed to plead guilty to state charges in Florida for soliciting prostitution. In July 2019, following an investigation by the Miami Herald that also scrutinized the integrity of the government’s probe, Epstein was indicted on federal charges of sex trafficking of minors. A month later, he died by suicide in his jail cell, federal law enforcement authorities said, while awaiting trial. Epstein’s death led to a swirl of renewed interest among Trump supporters, which in recent months has verged into an obsession. Last year, while still on the campaign trail, Trump vowed to “declassify” material in the government’s possession pertaining to Epstein. Before Pam Bondi was nominated as attorney general by Trump, she insisted that the public had a right to know more details about the case. “If people in that report are still fighting to keep their names private,” she said on Fox News last year, “they have no legal basis to do so, unless they’re a child, a victim, or a cooperating defendant.” In January, Kash Patel, the FBI director, told a Senate Committee during his confirmation hearing that he’d ensure “the American public knows the full weight of what happened.” Then on Feb. 27, during a highly publicized event at the White House, Bondi rolled out what the Justice Department referred to as the “first phase” of the release of the Epstein files. It was attended by former Pizzagate provocateur Jack Posobiec and other far-right influencers. They were given binders labeled “The Epstein Files” and “The Most Transparent Administration in History” that contained about 200 pages of documents that Bondi characterized as “declassified.” She also suggested that the records would contain previously undisclosed details about Epstein. Instead, Bondi’s big Epstein files party was a bust. It turned out the documents she called declassified, which included pages from Epstein’s infamous “black book,” had been previously released, most recently during the criminal trial of Ghislaine Maxwell four years earlier. (The black book revealed Trump’s name and the names of his wife, Melania, and other family members.)  A page from Epstein’s “black book,” containing the names of various contacts, which included Trump. Trump’s followers were irate. Bondi was angry, too. She fired off a letter to FBI Director Patel demanding to know why the bureau failed to provide her with the thousands of pages of documents related to the Epstein investigation and indictment she requested. She wanted answers from Patel, and accountability. What happened next kicked off a new phase in the Epstein saga. As I reported in the March 28th edition of FOIA Files, Patel directed FBI special agents from the New York and Washington field offices to join the bureau’s FOIA employees at its sprawling Central Records Complex in Winchester, Virginia and another building a few miles away. They were instructed to search for and review every single Epstein-related document and determine what could be released. That included a mountain of material accumulated by the FBI over nearly two decades, including grand jury testimony, prosecutors’ case files, as well as tens of thousands of pages of the bureau’s own investigative files on Epstein. It was a herculean task that involved as many as 1,000 FBI agents and other personnel pulling all-nighters while poring through more than 100,000 documents, according to a July letter from Senator Dick Durbin to Bondi. Senior officials at the FBI’s Record/Information Dissemination Section, which handles the processing of FOIA requests, pushed back on the directives. Michael Seidel, the section chief of RIDS who worked at the FBI for about 14 years, was quite vocal, the three people familiar with the matter told me. Patel blamed him for the failure to send all of the Epstein files to Bondi. Then, a couple of months ago, Seidel was told he could either retire or be fired, according to the people. He chose the former and quietly left the FBI, the people said. The details related to Seidel’s exit haven’t been previously reported. Seidel could not be reached for comment. The FBI employees reviewed the records using the Freedom of Information Act as their guide for deciding what information should be withheld. That alone isn’t uncommon. In the FOIA, Congress established nine exemptions as a way to balance the public’s right to know against the government’s need to protect sensitive interests, such as national security, official deliberations, ongoing law enforcement proceedings or privacy. When such competing interests arise in non-FOIA matters, those exemptions are often applied even if the exact language set forth in the FOIA statute doesn’t appear in the final record. For example, when congressional committees request documents from, say, the FBI or the Justice Department, FOIA analysts and contractors are brought in to review the records and apply redactions in accordance with the law. When the DOJ prepared to publicly release former Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report on Russia’s interference in the 2016 election, FOIA exemptions were used to determine what information should be withheld. While reviewing the Epstein files, FBI personnel identified numerous references to Trump in the documents, the people familiar with the matter told me. Dozens of other high-profile public figures also appeared, the people said. (The appearance of Trump’s name or others in the Epstein files is not evidence of a crime or even a suggestion of wrongdoing.) In preparation for potential public release, the documents then went to a unit of FOIA officers who applied redactions in accordance with the nine exemptions. The people familiar with the matter said that Trump’s name, along with other high-profile individuals, was blacked out because he was a private citizen when the federal investigation of Epstein was launched in 2006. In particular, the reviewers applied two FOIA exemptions to justify their redactions. The first, Exemption 6, protects individuals against “a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.” The Supreme Court has said the exemption protects "individuals from the injury and embarrassment" that would result from the disclosure of personal information in possession of the government. The second, Exemption 7(C), protects personal information contained in law enforcement records, the disclosure of which “could reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.” A White House spokesperson would not respond to questions about the redactions of Trump’s name, instead referring questions to the FBI. The FBI declined to comment. The Justice Department did not respond to multiple requests for comment. If you’re surprised by the revelation that the FBI used privacy exemptions to withhold the name of a sitting president, you’re not alone. However, it’s common practice for government agencies to redact names on privacy grounds, even when they’re clearly public figures like Trump. I lost count of how many times the government invoked a privacy exemption in response to my FOIA requests to deny releasing records on public figures and government officials. More than a decade ago, I requested records from the FBI on Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks. The FBI cited privacy in denying my request and said I needed to get a privacy waiver signed by Mohammed himself. In 2016, I requested all of the FBI’s files on Trump prior to his presidential campaign. In response, the FBI neither confirmed nor denied that any records existed, based on the same two privacy exemptions. I ended up suing the bureau and modifying my FOIA request to center on Trump’s businesses. That allowed me to overcome the privacy exemption and report this story.

Another noteworthy example: The DOJ cited the same exemptions to justify withholding Donald Trump Jr’s name from the Mueller report. (My attorneys and I believed it was an improper use of the privacy exemption. We fought to get his name unredacted and won.) But the reality is, there’s established precedent to protect the identities of private citizens named in law enforcement files no matter how famous they are. It’s a really high bar to overcome. The privacy exemptions were designed to prevent the government from releasing personal information on individuals just because it wants to. Of course, the government does break the law sometimes. Before withholding records under Exemption 6, government agencies are supposed to conduct a balancing test to determine if their release would significantly contribute to the public’s understanding of the operations or activities of the government. It’s way more difficult to make a case for disclosure when names are also withheld under Exemption 7(C). That’s partly because the DOJ has said that the very “mention of an individual’s name in a law enforcement file will engender comment and speculation and carries a stigmatizing connotation.” Also, FOIA case law has established that the names of private individuals contained in law enforcement files will not be released unless they have to be in order to confirm government misconduct. “Unless there is compelling evidence that the agency denying the FOIA request is engaged in illegal activity, and access to the names of private individuals appearing in the agency's law enforcement files is necessary in order to confirm or refute that evidence, there is no reason to believe that the incremental public interest in such information would ever be significant,” the DC Circuit Court of Appeals wrote in 1991 deciding a key FOIA case. Ever since, this precedent has been a thorn in the side of the FOIA community. It’s also the reason Trump's name in the Epstein files is likely to remain under wraps. Disclosing Trump’s name, the people familiar said, would neither shed light on how the FBI conducted its investigation into Epstein, nor that the FBI engaged in illegal activity. That brings us up to today. After the FBI redacted the Epstein files, they were sent to Bondi. (Media reports said Bondi briefed Trump at the White House in May and told him he was named in the files.) Then, on July 8, the Justice Department and FBI released an unsigned joint statement that said the FBI collected more than 300 gigabytes of data and physical evidence related to the Epstein investigation. However, the promises of “transparency” made earlier by Bondi and Patel didn’t materialize. “While we have labored to provide the public with maximum information regarding Epstein,” the statement read, “it is the determination of the Department of Justice and the Federal Bureau of Investigation that no further disclosure would be appropriate or warranted.” The officials added that “much of the information is subject to court-ordered sealing.” The statement ignited a firestorm on social media. Trump's most ardent supporters were furious with Bondi and the president. They said it was a cover-up. The influential podcaster Joe Rogan recently accused the administration of “trying to gaslight” his supporters over Epstein. Trump, meanwhile, has tried to contain the fallout. He lashed out at his base in a series of posts on his social media platform, Truth Social, and blamed Democrats for the “fake” Epstein scandal. Here’s the bottom line: The FBI's behind-the-scenes decision-making suggests that the chances of aliens resurrecting JFK are greater than Trump’s name ever being unredacted from the Epstein files. Of course, Trump could agree to let his name out or sign a privacy waiver. Or, when he—and everybody else named in the files—eventually dies, most of their privacy rights will disappear. Got a tip about the Epstein files or a document you think I should request via FOIA? Send me an email: jleopold15@bloomberg.net or jasonleopold@protonmail.com. Or send me a secure message on Signal: @JasonLeopold.666. |