| I’m Chris Anstey, an economics editor in Boston. Today we’re looking at the potential for restrictions on the financial side of US trade. Send us feedback and tips to ecodaily@bloomberg.net or get in touch on X via @economics. And if you aren’t yet signed up to receive this newsletter, you can do so here. - ECB chief Christine Lagarde emphasized the need to unite Europe’s capital markets.

- In Washington, Donald Trump’s search for a Treasury secretary remains in flux.

- Japan’s cabinet approved a stimulus package that’s slightly bigger than last year’s.

Much, if not most, of the focus on the incoming Trump administration’s international economic policy has been on tariffs on imported goods. But don’t dismiss the potential for more restrictive measures in finance: namely, capital controls. So says Freya Beamish, chief economist at TS Lombard. The basic logic: Restrictions on foreign investment in dollars could help rebalance trade, because other countries would have nowhere to put their export earnings — unless they bought American goods. As a lesson for keeping an open mind as to what might come, Beamish cites the case of the late British politician Sidney Webb. After his party was no longer in power, he was famously credited with saying “nobody told us we could do that” when a subsequent government removed the pound from the gold standard in 1931. Read More: Trump Tariff Plans Expected to Deliver High Drama, Bumpy Rollout Similar thoughts might have occurred to former officials in Washington when the first Trump administration jacked up tariff rates on Chinese, and many other, goods imports — using presidential authority in ways that hadn’t been employed, at least to the same extent, in the past. In the second term, tariffs will likely be “the first line of attack,” once again, Beamish wrote in a note this week. At least with China, the risk is that the trade gap persists nonetheless, Beamish says. Keep in mind that Trump’s first US trade representative, Robert Lighthizer, has been advocating for a complete elimination of the deficit. The gap in 2023 was $279 billion. That’s a whole lot to make up. Chinese authorities may not do enough to bolster domestic demand to help reorient away from net exports. Another problem is that tariffs tend to drive up the dollar, making trading partners’ exchange rates all the more competitive — as Scott Bessent, a hedge fund manager who advised Donald Trump’s campaign and has been a candidate for Treasury secretary, acknowledged earlier this month. “Trump simply cannot have both tariffs and an escape from the strong dollar unless he considers the capital account and that would be a game changer,” Beamish says. The flip side of the trade surplus is a financial deficit — China recycles its earnings into dollar assets. And that’s something that Washington has enormous sway to change. Citigroup back in 2019 labeled blocking Chinese access to its financial markets as “the most extreme US potential retaliation” against Beijing. As with tariffs, there’s legislation that grants the president executive authority. In particular, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, can be invoked for a variety of measures, including financial sanctions as well as tariffs. “Telling the rest of the world, that the Treasury does not want their funds might seem like shooting oneself in the foot. But it has to be considered as a tail risk,” Beamish says. “Capital controls seem likely at least to gain popularity as an idea, and even mere ideas can cause some volatility down the line.” - Germany’s economy expanded less than initially reported in the third quarter, while private-sector business activity in France plunged at the quickest rate since the start of the year.

- Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee sees interest rates moving “a fair bit lower.”

- UK consumer confidence posted a surprise increase in November after the budget ended uncertainty over the tax and spending plans of the new Labour government, a survey found.

- Indonesia President Prabowo Subianto said the government plans to retire all the nation’s coal power plants within 15 years.

- Japan’s key inflation gauge held above the central bank’s target.

- Singapore’s housing market is heating up again after a blockbuster month.

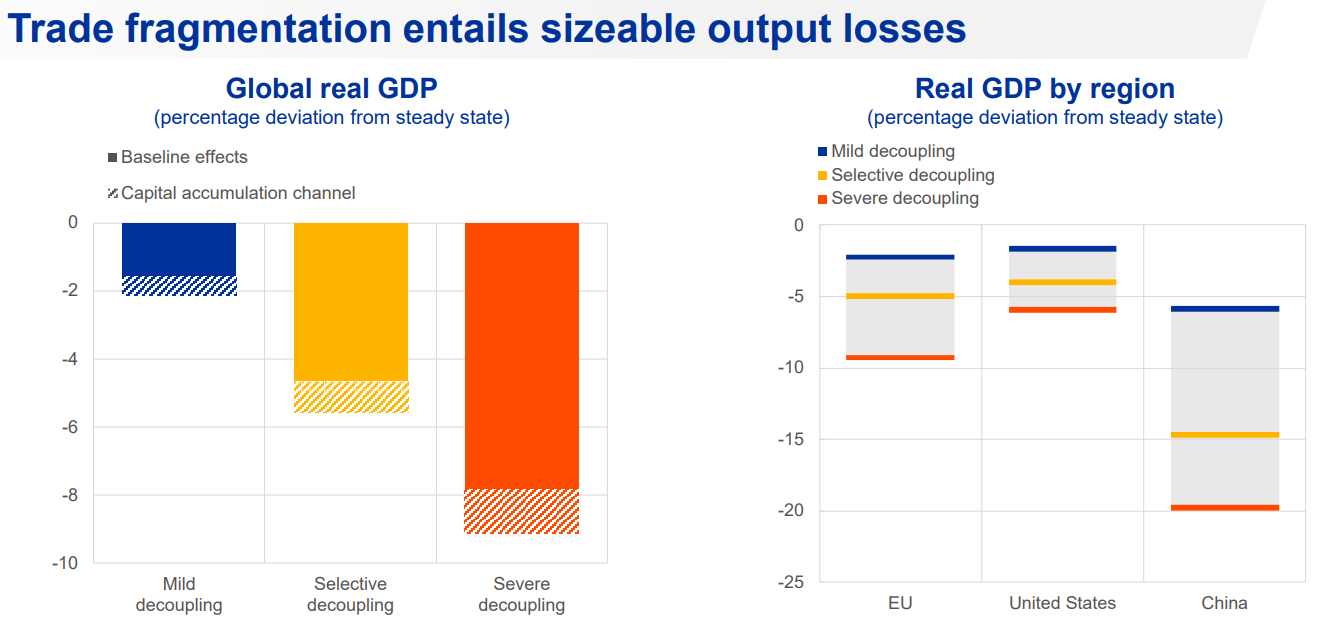

Any magnitude of global trade decoupling hurts global GDP, although different trading nations see notably different results, according to analysis cited by ECB Chief Economist Philip Lane this week. Even under “mild” decoupling — involving partial trade restrictions on all sectors — world GDP would see roughly a 2 percentage point negative deviation, including the impact on capital accumulation from trade. Under “severe” decoupling, the loss extends to greater than 8 percentage points over time, Lane’s charts showed. In “selective” decoupling, which features a full ban on just products deemed more prone to “being weaponized,” the hit approaches 6 percentage points.  Source: ECB Chief Economist Philip Lane presentation The severe scenario would involve a “full trade ban” on all sectors. For the US, the loss would be in excess of 5 percentage points, with the European Union seeing a near 10-percentage-point hit and China getting walloped by 20 percentage points, a forthcoming Bank of Italy study shows, according to Lane. |