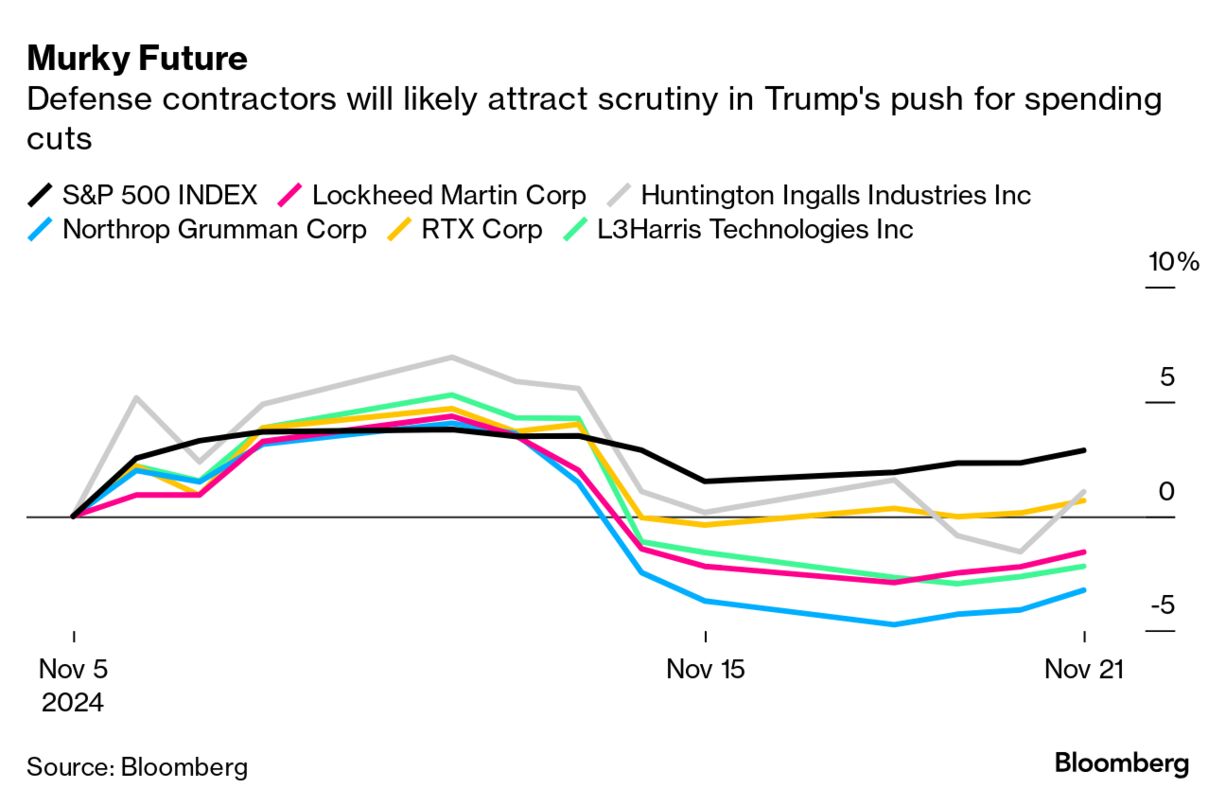

| Have thoughts or feedback? Anything I missed this week? Email me at bsutherland7@bloomberg.net. Also a programming note: There will be no Industrial Strength next week because of the Thanksgiving holiday. Look for the next one on Dec. 6. To get Industrial Strength delivered directly to your inbox, sign up here. Conventional wisdom says that Republican presidents tend to be better for the business of bullets, bombs and fighter jets. The actual data is more muddled, suggesting that the geopolitical threat environment plays a bigger role in determining defense spending than who sits in the White House. But nevertheless, little about a second Trump administration is expected to be conventional. A custom Bloomberg basket of nine large US defense contractors has declined more than 4% since Donald Trump was declared the winner of the US presidential election, led by declines at TransDigm Group Inc. and General Dynamics Corp. That compares with a 3.2% return for the S&P 500 Industrial Index and a 2.9% rally for the broader benchmark through Thursday.  While the US defense budget did grow during his first term — by about 29%, according to Melius Research — this time around, Trump has pledged to slash government spending, even going so far as to put Elon Musk and financier Vivek Ramaswamy in charge of an efficiency commission tasked with finding potential cuts. Defense is the largest bucket of discretionary spending in the US budget, and the industry has long faced criticism for overcharging the government. The Pentagon’s inspector general recently said the Air Force paid a 7,943% markup for Boeing Co. soap dispensers, and it’s previously said TransDigm collected $20.8 million in excess profit on spare parts sold to the Defense Department from early 2017 to mid-2019. “We expect massive cuts among federal contractors and others who are overbilling the federal government,” Ramaswamy said in a recent interview with Fox News. Defense contracts are binding and companies seek multi-year commitments from the government before making necessary manufacturing investments. But contracts typically do have clauses that allow for termination for convenience — which means the government cancels the deal but covers the company’s costs — or for cause in the event that deliveries are behind schedule, expenses have ballooned or performance otherwise falls short of expectations.

Trump got personally involved in the details of defense contracts during his first term: He pressured Boeing into offering a discount on the Air Force One fleet (a contract on which the company has subsequently racked up nearly $3 billion in losses) and also took credit for negotiating a price cut on Lockheed Martin Corp.’s F-35 program that in reality reflected preexisting cost control efforts and a bulkier order of jets over which to spread expenses.  “There’s that chaos factor,” says Vertical Research Partners analyst Rob Stallard. There’s a risk with Trump that a company or a lobbyist gets in his ear and he suddenly decides certain defense projects should be prioritized over others, Stallard said. Read more: ‘Nobody Knows What’s Going to Happen’: CEOs Brace for More Trump In addition to being a major backer of Trump’s campaign, Musk is also still the chief executive officer of Tesla Inc. and SpaceX, which has defense contracts for its rockets and Starlink satellites worth billions of dollars. “I think that there's legitimate concern,” Representative Seth Moulton, a Democrat from Massachusetts and a frontline Iraq war veteran who serves on the House Armed Services committee, said in an interview. “If you're a defense contractor whose name doesn't end in X, you're probably worried — for good reason.” The Department of Government Efficiency that Trump plans to set up isn’t an actual agency with any real unilateral power. Ripping up contracts en masse, while theoretically possible, would spark widespread pushback on national security concerns amid a need to replenish US weapons stockpiles and ready the country for any future conflicts, says Scott Mikus of Melius Research. Congress will have the ultimate say over defense spending, and it has plenty of experience protecting legacy programs that not even the Pentagon wants anymore.  The Air Force, for example, continues to wrangle with lawmakers over the future of an A-10 Warthog fleet that it says is a poor fit for the current threat environment, while Congress has also consistently thwarted the Navy’s efforts to retire old or costly-to-maintain ships — largely because shipyards create jobs. Boeing’s Chinook helicopter usually gets a plus-up in the defense budget, in part because it’s manufactured in Pennsylvania, a critical swing state, says Mikus. “The defense contractors aren't stupid. They know that if you want to protect your program, spread the supply chain and the economic impacts across the country as much as you can,” he said. But as Trump’s first term showed, just the public spectacle of criticism can be disruptive. Already, defense contractors were facing at best a low-growth spending environment. The ballooning US deficit may eventually matter again for bond investors, particularly if Trump pushes ahead on inflationary policies including across-the-board tariffs. Interest expenses on federal debt are set to exceed the defense budget this year for the first time in modern history, according to the Congressional Budget Office. In the event that deficit concerns do reemerge, cuts will have to come from somewhere. A debt ceiling deal struck last year between President Joe Biden and House Republicans caps the defense budget growth through at least fiscal 2025 — with an exception for supplemental spending bills. The lion’s share of the $95 billion supplemental security assistance package that Biden signed in April was earmarked for Ukraine. Both Trump and Vice President-elect JD Vance have criticized US support for Ukraine’s defense against Russia’s invasion and called for an end to the war. They have offered little detail on what that would mean in practice — both for Ukraine and for the US defense contractors that have been investing in more manufacturing capacity to meet that country’s military needs and replenish weapons stockpiles in America. Within Congress, “I don’t think there’s a majority that wants a significant spending increase. I don’t think there’s a majority that wants cuts either” to the defense budget, Stallard of Vertical Research said. “There is a limit to what the US system will allow — assuming Trump doesn’t throw the whole thing out the window.” The combined effects of pulling back support from Ukraine and slapping tariffs on America’s allies and foes alike — as Trump has threatened to do — will likely only deepen the resolve of European leaders to buy more military equipment from European suppliers and reduce their dependence on America. That will still leave plenty of international business for US defense contractors as other allies in the Middle East and Asia have much more limited domestic military expertise. It will also take time for Europe to accelerate investments in its defense industrial base. Key European countries may need to double their defense spending to address the challenge of Russia’s aggression and the possibility of less US support, according to a Bloomberg Intelligence analysis. Read more: EU Needs to Get Serious About Its Defense Funding: Editorial But longer term, an inward shift in Europe could tee up a diminished opportunity set for US weapons makers. US defense contractors are already taking some steps to prepare for such a scenario, including by exploring co-production deals whereby American-designed equipment is assembled or manufactured in an allied country. Lockheed Martin last year established collaboration frameworks with German and Polish manufacturers for production of rocket launchers and components. The F-35 fighter jet was also designed to be an international partnership, with final assembly lines in Italy and Japan. “A lot of those co-production plans are relatively still in their infancy,” Mikus of Melius Research said. “But that is the way it is going. It's also just a supply-chain resilience thing, too. It's not a good idea to have all of one product manufactured in one location.” “We're positioned really well. We rely heavily on our highly skilled employees in the US to design and build high-quality, the most technologically advanced equipment in the world. And as a result of that, greater than 75% of all products that we sell in the US are assembled here in the US.” — Deere & Co. CEO John May May made the comments on Deere’s earnings call this week in response to a question about the potential impact of tariffs under the incoming Trump administration. On the campaign trail, Trump had pledged to slap tariffs of 200% on Deere products if the company proceeded with plans to shift manufacturing work to Mexico. He then claimed the company had reversed course. Deere in October said that wasn’t true. The company earlier this year announced it’s acquiring land in Ramos, Mexico, to build a new facility that by 2026 will take on production of mid-frame skid-steer and compact-track loaders that’s currently handled by its plant in Dubuque, Iowa. In 2022, Deere announced plans to move work on tractor cabs to Mexico from Waterloo, Iowa, amid challenges attracting labor. Still, Deere has 30,000 employees in the US located in 60 facilities across 16 states, May said. It’s the kind of job-heavy pitch that worked in Trump’s transactional first term. And it just may work again. Read more: Musk Is Outlier in Pausing Mexico Factory Deere's forecast for 2025 profit was weaker than analysts had expected but the shares rallied to a more than one-year high on optimism that the worst of a slump in demand for agricultural equipment may be approaching as dealers make progress on clearing out bloated inventories. Spirit Airlines Inc. officially filed for bankruptcy this week, just before the busy holiday travel season kicks off. The company aims to continue operating as normal through the bankruptcy process, which it expects to complete in the first quarter of 2025. In a message to customers this week, Spirit encouraged flyers to feel comfortable booking flights “now and in the future.” It’s still possible that Spirit could combine with another airline. The company had initially agreed to sell itself to Frontier Group Holdings Inc. before accepting a higher offer from JetBlue Airways Corp., a deal which was ultimately blocked on antitrust grounds. “We suspect Frontier will keep ongoing tabs on Spirit and would be interested in many of its assets depending on price,” Conor Cunningham, an analyst at Melius Research, wrote in a note. United Airlines Holdings Inc. could also be interested in Spirit’s Florida operations, while JetBlue may want its East Coast network, he said. Honeywell International Inc. agreed to sell its face mask and other personal protective gear business for about $1.3 billion to private equity firm Odyssey Investment Partners. The company had previously said it intended to divest this business, along with a planned spinoff of its advanced materials arm. Activist investor Elliott Investment Management subsequently disclosed a more than $5 billion stake in the company and is pushing for a bigger breakup of Honeywell's aerospace and automation businesses.

Berry Global Group Inc., which makes plastic bottles, containers and bags, agreed to sell itself to rival packaging company Amcor Plc for $8.4 billion, plus the assumption of a nearly equal amount of debt. The all-stock transaction values Berry Global at roughly 10% premium to where the shares were trading before news of the deal. Berry Global earlier this month completed a Reverse Morris trust combination of its health, hygiene, nonwoven packaging and films business with Glatfelter Corp. Berry Global acquired British packaging company RPC Group Plc in 2019 in a roughly $6 billion deal that significantly swelled its debt load.

Air Products and Chemicals Inc. faces a proxy fight after activist investor Mantle Ridge nominated enough directors to replace the industrial gas company’s entire board. The activist slate comes after Air Products announced its own refresh of the board ahead of an annual shareholder meeting. Another activist investor, D.E. Shaw & Co., is also seeking changes at the company but isn’t planning to nominate a board slate, Bloomberg News has previously reported. The investors want Air Products to review its approach to capital investment, refresh its board, overhaul executive compensation and spell out a succession plan for CEO Seifi Ghasemi, who at 80 years old is one of the oldest CEOs among S&P 500 companies. |