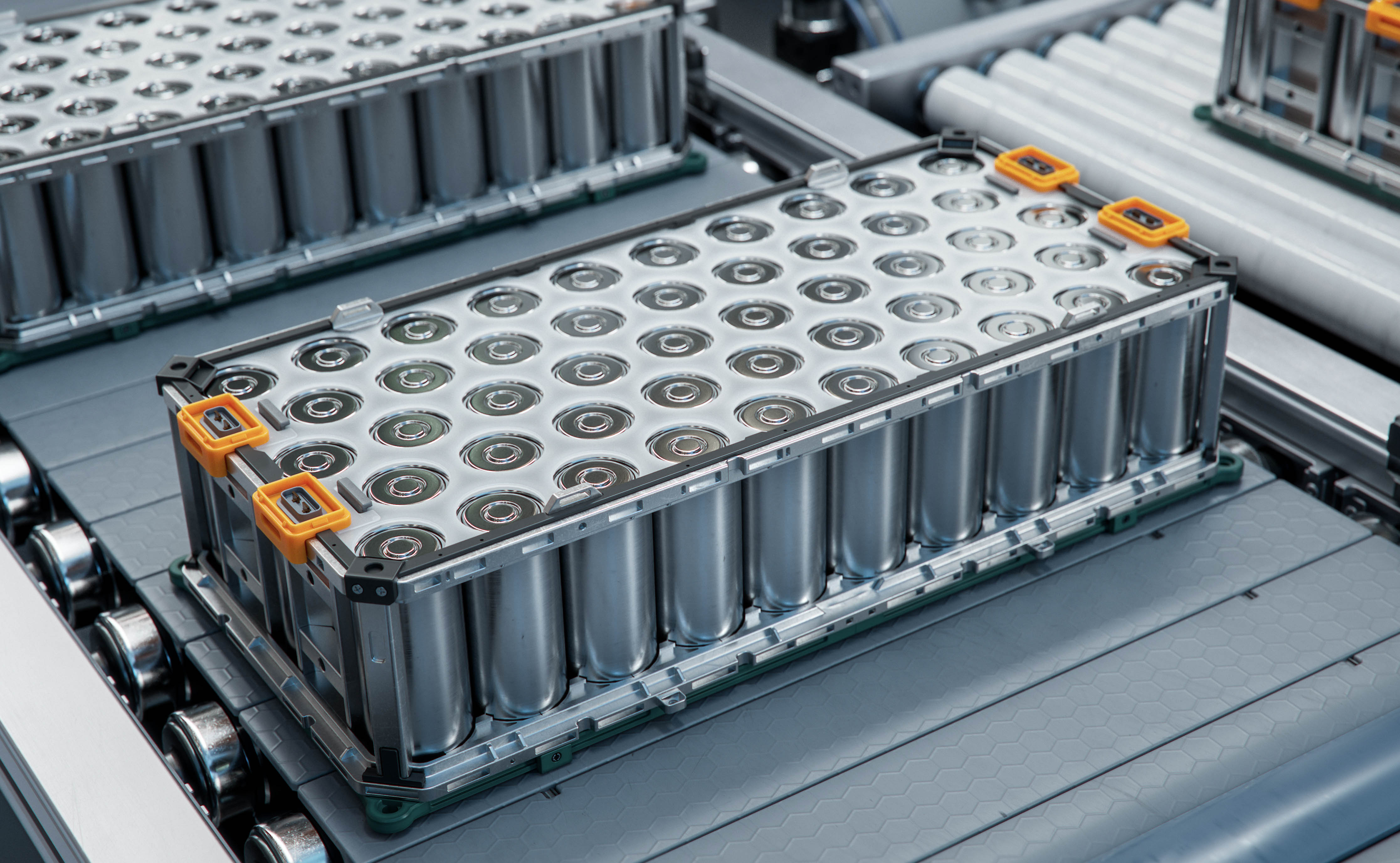

| Thanks for reading Hyperdrive, Bloomberg’s newsletter on the future of the auto world. Read today’s featured story in full online here. A couple of hours west of Tokyo by bullet train, in the midsize town of Mizunami, a shuttered middle school provides Japan’s carmakers with a different kind of education. A reverse-engineering company called Caresoft Global has turned the old junior high into a laboratory for electric-vehicle design. It pulls apart cars to study the innovations within, devise cost-saving proposals and pitch them to rival automakers. Some visiting clients study piles of parts in old classrooms, where blackboards are still dusted with chalk. Over in a room that once stored volleyballs, others review data gleaned from high-energy X-rays. And in what used to be the gym, there’s good reason for Toyota, the world’s leading car manufacturer, to be worried.  Caresoft facility with various cars makers products Photographer: Shiho Fukada for Bloomberg Businessweek On a hardwood floor streaked with memories of three-pointers and roll shots, the Caresoft team has laid out the disassembled hulks of a Tesla Model Y, a BYD Seal and more than a dozen other electric cars. In comparing their parts, the most important metric is weight reduction. For the electric business to keep growing, the cars need to better compete with gas-guzzlers on range. Most every design decision must take into account whether it makes the car lighter. As a basic example, consider one component: Toyota part #55330-42410, a 20-pound steel bar, known by engineers as a cross-car beam. The beam holds the steering wheel and dashboard instruments in place and helps protect the cabin during a collision. This part is inside the bZ4X, the Toyota brand’s only global, mass-market fully electric car, because it’s of a tried-and-true design used in countless other models. Today’s standard cross-car beam is the product of incremental improvements made across decades, and most versions of it have wound up under the hoods of internal combustion cars. This is a testament to the Toyota Production System, which continuously refines even the tiniest details of individual auto parts. Over untold iterations, the beam has been designed to keep the vibrations of an internal combustion engine from making their way to the passengers. But electric motors don’t vibrate, and steel is heavy. These are among the reasons why Tesla and BYD, the top makers of battery-electric vehicles, manufacture similar beams out of plastic. Theirs weigh only about 14 pounds, according to Caresoft, and they’re both cheaper and easier to install.  A Toyota bZ4X at the New York International Auto Show in March 2024. Photographer: Gabby Jones/Bloomberg It’s a change that sounds so simple once you hear it, and intuitive, perhaps, if you’ve never dealt with a gas engine. If you’ve spent a lifetime thinking in terms of micro-improvements — the core of kaizen, the philosophy that underpins the Toyota Production System, or TPS — it’s an insight that might well prove elusive. “You cannot kaizen yourself from an ICE vehicle to a BEV,” says Caresoft President Terry Woychowski, a former General Motors executive. “That is the dilemma for Toyota.” Outside of EVs, Toyota is doing not only fine, but great. While it has lagged behind even old-school competitors in transitioning its production lines to all-electric models, the past year made that look smart. Demand for electric cars continued to grow, but not as quickly as the $3 trillion auto industry had wagered while pouring untold billions of dollars into their development. Toyota’s products, meanwhile, were about two-thirds internal combustion, one-third hybrid and 0.1% electric, and it cleaned up. It pulled further ahead of its longtime rivals (Volkswagen, Hyundai, GM) and is estimated to have sold more than 11 million vehicles in 2024, compared with 1.8 million for Tesla and 4.3 million for BYD (1.8 million of which were electric). Chairman Akio Toyoda has insisted on a “multi-pathway” strategy, which in practice has meant hybrids, gas-guzzlers and even hydrogen-powered cars. Although Toyoda, who’s 68, ceded the role of CEO to former Lexus boss Koji Sato in 2023, the chairman’s word remains the one that matters. “Toyota’s 11 million units are the sum total of having customers in various countries and many models,” says Tatsuo Yoshida, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. “Sustaining such a huge level of production is by no means easy. Many other automakers find it difficult to get past 6 million.”  Akio Toyoda with electric prototypes at the company’s Tokyo showroom in 2021. Source: Toyota In the longer term, though, Toyoda’s aversion to a fundamental rethink of the family business may limit the company’s ability to dream up the cars of the future. TPS has conditioned Toyota — and its shameless imitators the world over — to silo specialized engineers, concentrate on streamlining assembly processes and outsource as many components as possible to outside suppliers. These moves helped it maximize the efficiencies of a mature, commoditized hardware market. For hardware that’s just getting started, they’re often liabilities. “Unless we embrace a new way of thinking, we will never be able to catch up,” says Shinichi Sasaki, a former executive vice president at Toyota who now runs the Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers. — By Reed Stevenson and Chester Dawson  Source: Getty Images Battery prices are set to fall for a third straight year, though not nearly as much as in the past, due to rising trade tensions and metals prices, according to analysts at BloombergNEF. Lithium-ion battery prices are forecast to drop 3% to around $112 per kilowatt-hour, the analysts found. That compares to declines of 20% in 2024 and 13% in 2023. Ever-cheaper batteries are key to help drive demand for electric vehicles. This year, a key variable will be the degree of protectionism in trade policies pursued by President-elect Donald Trump. Any additional tariffs would add to those imposed by President Joe Biden, who targeted areas including batteries, solar cells and EVs. |